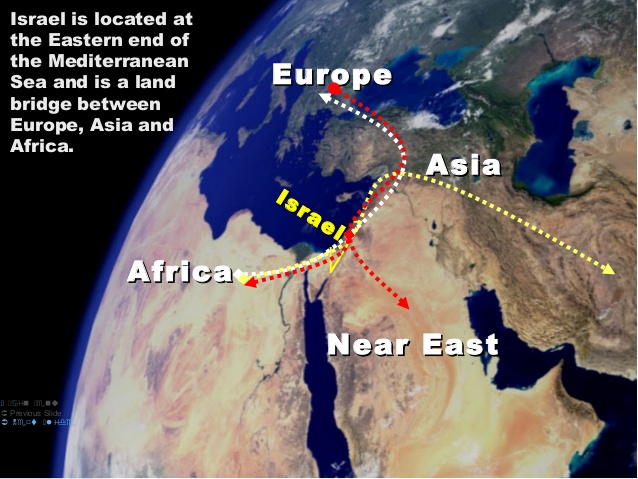

The nation of Israel, in the land of Canaan, was God’s institution for His worship, for passing on the truth about the coming Messiah, and for preaching the gospel to the nations both in picture through the sacrificial system and through direct calls to the nations to repentance and faith in Christ in texts such as: “Kiss the Son, lest he be angry, and ye perish from the way, when his wrath is kindled but a little. Blessed are all they that put their trust in him” (Psalm 2:12); see Truth from the Torah here for more information). Have you ever thought about the location in which God put the land of Canaan in relation to His purpose that Israel be a light to the nations?

The location of Israel was perfect for reaching Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Near East. It was also the center of international trade routes. Have you thought about how much less effective of a location the nation would have had if God had put it, say, in Madagascar?

Fairbairn comments as follows:

Proceeding, however, to a closer view of the subject, we

notice, first, the region actually selected for a possession of an inheritance

to the covenant people. The land of Canaan occupied a place in the ancient

world that entirely corresponded with the calling of such a people. It was of

all lands the best adapted for a people who were at once to dwell in

comparative isolation, and yet were to be in a position for acting with effect

upon the other nations of the world. Hence it was said by Ezekiel1

to have been “set in the midst of the countries and the nations” the umbilicus terrarum. In its immediate

vicinity lay both the most densely-peopled countries and the greater and more

influential states of antiquity,—on the south, Egypt, and on the north and east,

Assyria and Babylon, the Medes and the Persians. Still closer were the maritime

states of Tyre and Sidon, whose vessels frequented every harbor then known to

navigation, and whose colonies were planted in each of the three continents of

the old world. And the great routes of inland commerce between the civilized

nations of Asia and Africa lay either through a portion of the territory

itself, or within a short distance of its borders. Yet, bounded as it was on

the west by the Mediterranean, on the south by the desert, on the east by the

valley of the Jordan with its two seas of Tiberias and Sodom, and on the north

by the towering heights of Lebanon, the people who inhabited it might justly be

said to dwell alone, while they had on every side points of contact with the

most influential and distant nations. Then the land itself, in its rich soil

and plentiful resources, its varieties of hill and dale, of river and mountain,

its connection with the sea on one side and with the desert on another,

rendered it a kind of epitome of the natural world, and fitted it peculiarly

for being the home of those who were to be a pattern people to the nations of

the earth. Altogether, it were impossible to conceive a region more wisely

selected and in itself more thoroughly adapted, for the purposes on account of

which the family of Abraham were to be set apart. If they were faithful to

their covenant engagements, they might there have exhibited, as on an elevated

platform, before the world the bright exemplar of a people possessing the

characteristics and enjoying the advantages of a seed of blessing. And the

finest opportunities were at the same time placed within their reach of proving

in the highest sense benefactors to mankind, and extending far and wide the

interest of truth and righteousness. Possessing the elements of the world’s

blessing, they were placed where these elements might tell most readily and

powerfully on the world’s inhabitants; and the present possession of such a

region was at once an earnest of the whole inheritance, and, as the world then

stood, an effectual step towards its realization. Abraham, as the heir of

Canaan, was thus also “the heir of the world,” considered as a heritage of

blessing.1[1]

notice, first, the region actually selected for a possession of an inheritance

to the covenant people. The land of Canaan occupied a place in the ancient

world that entirely corresponded with the calling of such a people. It was of

all lands the best adapted for a people who were at once to dwell in

comparative isolation, and yet were to be in a position for acting with effect

upon the other nations of the world. Hence it was said by Ezekiel1

to have been “set in the midst of the countries and the nations” the umbilicus terrarum. In its immediate

vicinity lay both the most densely-peopled countries and the greater and more

influential states of antiquity,—on the south, Egypt, and on the north and east,

Assyria and Babylon, the Medes and the Persians. Still closer were the maritime

states of Tyre and Sidon, whose vessels frequented every harbor then known to

navigation, and whose colonies were planted in each of the three continents of

the old world. And the great routes of inland commerce between the civilized

nations of Asia and Africa lay either through a portion of the territory

itself, or within a short distance of its borders. Yet, bounded as it was on

the west by the Mediterranean, on the south by the desert, on the east by the

valley of the Jordan with its two seas of Tiberias and Sodom, and on the north

by the towering heights of Lebanon, the people who inhabited it might justly be

said to dwell alone, while they had on every side points of contact with the

most influential and distant nations. Then the land itself, in its rich soil

and plentiful resources, its varieties of hill and dale, of river and mountain,

its connection with the sea on one side and with the desert on another,

rendered it a kind of epitome of the natural world, and fitted it peculiarly

for being the home of those who were to be a pattern people to the nations of

the earth. Altogether, it were impossible to conceive a region more wisely

selected and in itself more thoroughly adapted, for the purposes on account of

which the family of Abraham were to be set apart. If they were faithful to

their covenant engagements, they might there have exhibited, as on an elevated

platform, before the world the bright exemplar of a people possessing the

characteristics and enjoying the advantages of a seed of blessing. And the

finest opportunities were at the same time placed within their reach of proving

in the highest sense benefactors to mankind, and extending far and wide the

interest of truth and righteousness. Possessing the elements of the world’s

blessing, they were placed where these elements might tell most readily and

powerfully on the world’s inhabitants; and the present possession of such a

region was at once an earnest of the whole inheritance, and, as the world then

stood, an effectual step towards its realization. Abraham, as the heir of

Canaan, was thus also “the heir of the world,” considered as a heritage of

blessing.1[1]

Learn from the location in which God put Israel His purposes of grace toward the entire world through His chosen people and His ultimate chosen Servant, the Lord Jesus Christ (Isaiah 42; 53; 61), and the perfection of all the Divine works.

1 Ch. 5:5.

1 Rom. 4:13.

[1]

Patrick Fairbairn, The Typology of

Scripture: Viewed in Connection with the Whole Series of the Divine

Dispensations, vol. 1 (London: Funk & Wagnalls Company,

1900), 332–333.

Patrick Fairbairn, The Typology of

Scripture: Viewed in Connection with the Whole Series of the Divine

Dispensations, vol. 1 (London: Funk & Wagnalls Company,

1900), 332–333.