Home » Search results for 'king james version' (Page 15)

Search Results for: king james version

If the Perfectly Preserved Greek New Testament Is the Textus Receptus, Which TR Edition Is It? Pt. 2

Many who looked at part one probably did not read it, but scrolled through the post to see if I answered the question, just to locate the particular Textus Receptus (TR) edition. They generally don’t care what the Bible says about this issue. They’ve made up their minds. Even if they hear a verse on the preservation of scripture, they will assume it conforms to textual criticism in some way. I’m sure they were not satisfied with the answer that the Words of God were perfectly preserved in the TR. That is what I believe, have taught, and explained in that first post. However, I wasn’t done. I’m going to give more clarity for which I didn’t have time or space.

In part one I said that I believe that scripture teaches that God preserved Words, not paper, ink, or a perfect single copy that made its way down through history. God made sure His people would have His Words available to live by. It is akin to canonicity, a doctrine that almost every knowing believer would say he holds. Some believers don’t know enough to say what they think on canonicity. I’ve written a lot about it on this blog, but normally professing Christians relate canonicity to the sixty-six books of the Bible, a canonicity of books. Scripture doesn’t teach a canonicity of books. It is an application of a canonicity of Words.

Along with the thoughts about the perfect preservation of scripture, perhaps you wondered if at any one time, someone would or could know that he held a perfect book in his hands. From what we read in history, that is how Christians have thought about the Bible. I remember first hearing the verbal plenary inspiration of scripture and thinking that it related to the Bible I used. Any other belief would not have occurred to me.

The condition of all of God’s Words perfectly in one printed text has been given the bibliological title of a settled text. Scripture also teaches a settled text to the extent that it was possible someone could add or take away from the Words (Rev 22:18-19; Dt 12:32), that is, they could corrupt them. You cannot add or take away a word from a text that isn’t settled. The Bible assumes a settled text. This is scripture teaching its doctrine of canonicity.

When we get to a period after the invention of the moveable type printing press, believers then expressed a belief in a perfect Bible in the copies (the apographa) that they held. They continued printing editions of the TR that were nearly identical, especially next to a standard of variation acceptable to modern critical text proponents. I’m not saying they were identical. I own a Scrivener’s Annotated Greek New Testament. However, all the Words were available to believers.

Editions of the Textus Receptus were published by various men in 1516, 1519, 1522, 1527, 1534, 1535, 1546, 1549, 1550, 1551, 1565, 1567, 1580, 1582, 1589, 1590, 1598, 1604, 1624, 1633, 1641, and 1679. I’m not going to get into the details of these, but several of these editions are nearly identical. The generations of believers between 1516 and 1679 possessed the Words of God of the New Testament. They stopped publishing the Greek New Testament essentially after the King James Version became the standard for the English speaking people. Not another edition of the TR was published again until the Oxford Edition in 1825, which was a Greek text with the Words that underlie the King James Version, similar to Scrivener’s in 1894. Believers had settled on the Words of the New Testament.

I believe the underlying Hebrew and Greek Words behind the King James Version represent the settled text, God’s perfectly preserved Words. I like to say, “They had to translate from something.” Commentators during those centuries had a Hebrew and Greek text. Pastors studied an available original language text to feed their churches. This is seen in a myriad of sermon volumes and commentaries in the 16th to 19th centuries.

Scripture teaches that the Holy Spirit would lead the saints to receive the Words the Father gave the Son to give to them (Jn 16:13; 17:8). Because believers are to live by every one of them, then they can know with certainty where the canonical Words of God are (Mt 4:4; Rev 22:18-19) and are going to be judged by them at the last day (Jn 12:48). This contradicts a modern critical text view, a lost text in continuous need of restoration.

True believers received the TR itself and the translations from which it came. They received the TR and its translations exclusively. Through God’s people, the Holy Spirit directed to this one text and none other.

The Uncertainty of the “Textual Confidence” View of Preservation of Scripture

For those reading, next week either Monday or Wednesday, I will provide as concise an answer as possible to the question, “Which TR?” I’ve answered this question before several times, but it’s usually just ignored, never answered. I’ve never had it answered. It’s asked as a gotcha question, then I give the answer, followed by silence. I’m going to try to do the best I’ve ever done at the answer.

**************************

A group of four men calling themselves The Textual Confidence Collective recorded seven podcasts for youtube. These men posted their first on Monday, July 11, 2022. The purpose of their gathering in Texas for these recordings was to persuade people of a new position on preservation of scripture. They call it “textual confidence.” They’ve given their own new position an enticing or attractive label, but it is still new.

Confidence sounds very good. Confidence in Collective parlance is akin to the word “trust.” I believe that’s what they mean by “confidence.” Placing confidence in someone or something is trusting it or trusting in it. In the scriptural use of the word “trust,” God does not call for confidence or trust in the uncertain. Uncertainty also does not bring biblical trust. Confidence relates to God, Who is always certain.

As a label, “Textual Confidence” definitely sounds superior to “Textual Doubt.” The four men testify they want to help Christians have confidence in the underlying text of their English translation of the Bible. They say it’s not a sure, settled text, and unlike their opponents, they’re honest. This admission of less than one hundred percent surety, they argue, engenders confidence. The text of scripture is something pure like Tide detergent, not 100%, but still good.

The Collective Confidence falls short of certainty. Three of the men replaced certainty with what they call confidence. The discovery of textual variants, that is, variations in hand copies, destroyed their certainty. This shows they do not stand on biblical presuppositions. They also listened to men who contradicted certainty. Now they are confident in the text without certainty about the words. They reject certainty and also want to push their uncertainty on others, bringing every church in the world to the same position, what they call “unity.”

The Collective also says they’re just telling the truth in contrast to people with differing positions, deceived or lying. Those who take their view — according to them — are very nice, super balanced, great with their rhetorical tone compared to the others. Part of this, they say about themselves, is their focus on Jesus and the gospel rather than on the text of scripture. This implies that supporters of other positions than theirs elevate the Bible above Jesus in an unbalanced and perverted way. The latter is an example of their tone.

Jesus said, “Thy Word is truth” (John 17:17). Delivering the teaching of scripture is truth. What the Bible says about itself is true. The existence of textual variants does not change the biblical doctrine of the preservation of scripture.

Many people have suffered for believing something different than they once did, including from family. No one will invite me to the same functions as Mark Ward. Certain doors close depending on what you believe. If you believe an error, the same thing will occur. I don’t condone a kind of mean or vicious form of separation that just cuts people off. I don’t practice that kind of separation either. Many evangelicals practice like this, even though they don’t even believe in biblical separation. Facing exclusion though doesn’t make a position right.

Two of the Collective testified to suffering from parents and siblings for changing positions on the Bible. I don’t think someone should hang on to a false position because they don’t want to lose their family. The Collective, however, treats this suffering as proof their new position is true and right. It doesn’t prove either position. No one should come to a conclusion for what’s right by comparing who suffers the most. This is common, however, among modern version proponents.

The Collective distinguishes their view from what they present as two false extremes, “textual skepticism” and “textual absolutism.” The men used Bart Ehrman as an example of the former. They weren’t clear who was the former, but I’m confident they’re talking about a wide range of King James Version and textus receptus advocates, anyone who is certain about the text of scripture.

A strong statement of the first podcast is that skepticism and absolutism come from the same place or are closer than what the audience may expect. The Collective says that an absolutist perspective turns people into skeptics more than skeptics do because of their defense of “every iota across the board.” I’m skeptical about this point, because the certainty that brings trust in scripture comes from what the Bible says about itself. Jesus defended every iota across the board.

Should people belief in the words of scripture as absolute, what someone might say is without variableness or shadow of turning? In other words, does the Word of God reflect the nature of God and its immutability? That is what scripture says about itself and it is what our spiritual forefathers passed down to us.

Modern textual criticism does not and has not increased trust in the inerrancy and authority of the Word of God. Since I’ve been alive, as the prominence of textual criticism grows, trust in scripture diminishes. Scriptural presuppositions on the other hand provide increasing spiritual strength through believing what God said, trusting in the Word of God as absolute authority. Greater faith proceeds from certainty, not uncertainty.

Mark Ward: KJVO “Sinful Anger,” the “Evasion” of the Confessional Bibliologians, and Success

Mark Ward wrote, Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible, which I read. He’s taken on a goal of dissuading people from the King James Version to use a modern version of the Bible. He also has a podcast to which someone alerted me when he mentioned Thomas Ross and me. I checked back again there this last week and he did one called, “Is My Work Working?” In it, he said he received three types of reactions to his work.

KJV “SINFUL ANGER”

Ward said he received more than 100 times praise than anything else. The next most reaction he said was “sinful anger” from KJV Onlyists. Last, he received the least, helpful criticism from opposition.

Critical text proponents very often use KJVO behavior as an argument. It does not add or take away from Ward’s position. Ward reads his examples of “sinful anger,” and well more than half didn’t sound angry to me. They disagreed with him.

My observation is that critical text advocates do not have better conduct. They disagree in a harsh manner and with ridicule. Ward himself uses more subtle mockery, sometimes in sarcastic tones. It just shouldn’t come as a point of argument. Many in the comment section of his podcast use sinful anger. Ward does not correct them or point out their sinful anger. It seems like Ward likes it when it points the other direction.

In these moments, Ward talks about his own anger. He finds it difficult not to be angry with these men. Why even mention it? Just don’t talk about it at all. Deal with the issue at hand. I’m not justifying actions of Ruckmanite types. They’re wrong too. Both sides are wrong. This is an actual argument though of critical text supporters — how they are treated. It comes up again and again, because they bring it up.

“EVASION” OF THE CONFESSIONAL BIBLIOLOGIANS

Ward says that few to almost none answer a main argument of his book, which he’s developed further since it’s publication. They don’t concede to his “false friends” with appropriate seriousness. He says they don’t think about false friends. He provides now 50 examples of these that appear many times in the King James Version. He includes the confessional bibliologians in this, which would be someone who believes in the superiority of the Textus Receptus of the New Testament. Their position might be perfect preservationism, Textus Receptus, confessional bibliology, or ecclesiastical text. He used the confessional title, referring to men like Jeff Riddle.

I’ve answered him in depth. Ward is just wrong. Hopefully calling him wrong isn’t considered sinful anger. “He said I was wrong!!” King James Version supporters all over buy Bible For Today’s Defined King James Version. It provides the meaning of those words in the margin. Lists of these from King James Version proponents are all over the internet, and books have been written by KJV authors (the one linked published in 1994) on the subject.

Ward says that every time he brings that up to Textus Receptus men, they sweep it away like it doesn’t matter, then turn the conversation to textual criticism. That’s a very simplistic way of himself swatting away the Textus Receptus advocate. They turn to textual criticism because the critical text and the Textus Receptus are 7% different. Many words differ. That matters more. It also denies the biblical doctrine of preservation.

The members of churches where men preach the KJV hear words explained. Sure, some KJV churches rarely preach the Bible. Talk about that. Where men preach expositional sermons from the KJV, relying on study of the original languages, they explain words to their people. They care. I have been one of those and the KJV doesn’t hurt our church in any way. Personally I read the KJV Bible twice last year and this year I’m on pace for one Old Testament and two New Testament.

SUCCESS

Is success how much praise one receives for what he does? Is that the measurement? That is a very dangerous standard of success. That is what Ward uses as his standard in his video. In Jeremiah 45:5, God told Baruch: “And seekest thou great things for thyself? seek them not.” We don’t succeed when we receive praise. We succeed when we are faithful to what God said, whether we’re praised or not. Seeking for praise is discouraged in scripture. Many faithful Bible preachers received far more harsh treatment than Ward. It’s not even close.

True success is finding what God says and doing it. It’s not success to turn a church away from the King James Version to a modern version, even if Ward supports that outcome.

1st Year New Testament Greek for Distance Students

Lord willing, I will be starting a 1st semester introductory Greek class which can be taken by distance students in the near future. If you are interested, please click here to contact me.

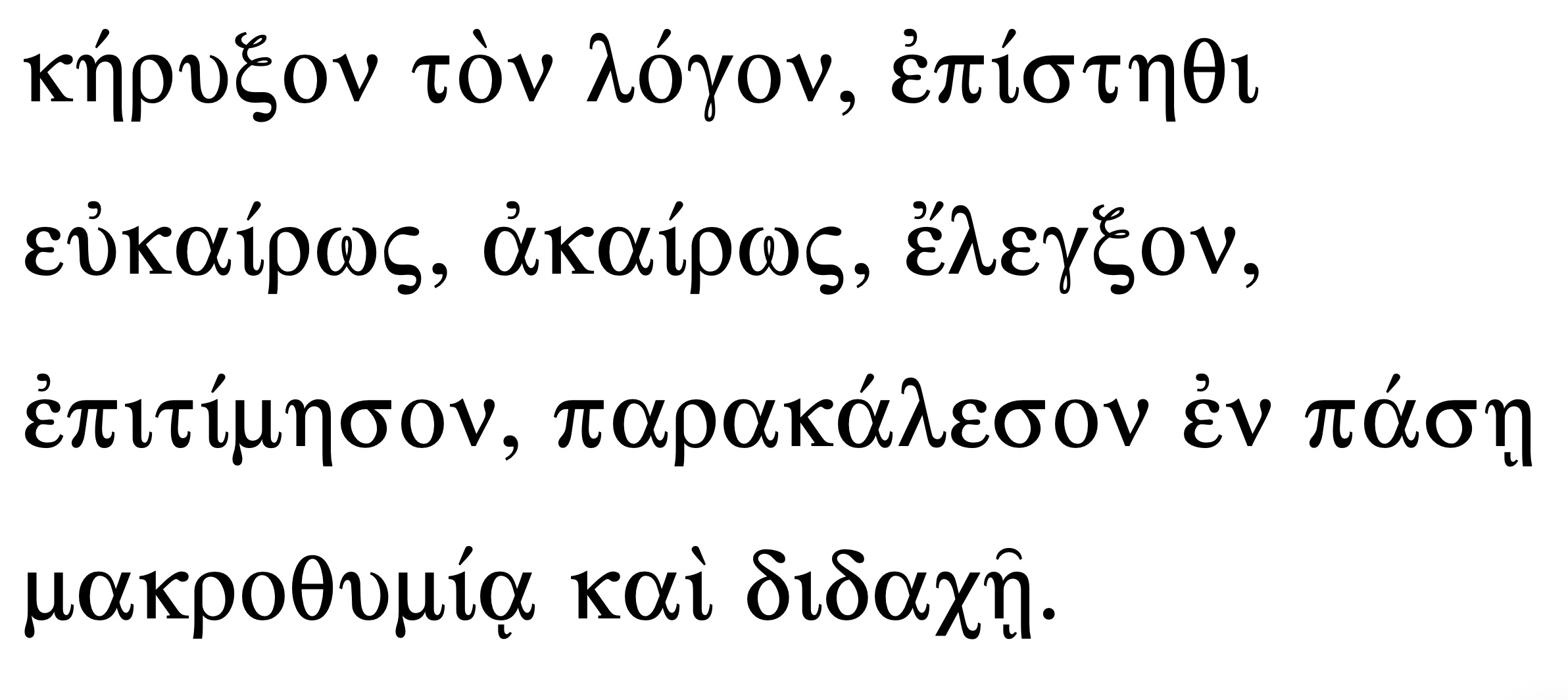

What Will I Learn in Introductory NT Greek?

We will be learning introductory matters such as the Greek alphabet, and then the entire Koine Greek noun system, after which we will get in to verbs in the indicative mood. A second semester to follow should cover the rest of the fundamentals of Greek grammar. At the end of the course, you will be well prepared to begin reading the New Testament on your own. You also will, I trust, have grown closer to the Lord through your growth in understanding and application of His Word, will have grown in your ability to read, understand, teach, and preach the Bible (if you are a man; women are welcome to take the class as well, as they should know God’s Word for themselves and their families and teach other women and children), and will be prepared to learn Greek syntax and dive deeper into exegesis and more advanced Greek study in second year Greek. You will learn the basics of New Testament Greek grammar, syntax and vocabulary, preparing you to translate, interpret and apply Scripture. Recognizing the importance of using the original languages for the interpretation of the New Testament, you will acquire a thorough foundation in biblical Greek. You will learn the essentials of grammar and acquire an adequate vocabulary.

The course should be taught in such a way that a committed high school student can understand and do well in the content (think of an “AP” or Advanced Placement class), while the material covered is complete enough to qualify for a college or a seminary level class. There is no need to be intimidated by Greek because it is an ancient language. Someone who can learn Spanish can learn NT Greek. Indeed, if you speak English and can read this, you have already learned a language—modern English—that is considerably more difficult than the Greek of the New Testament. Little children in Christ’s day were able to learn Koiné Greek, and little children in Greece today learn modern Greek. If they can learn Greek, you can as well, especially in light of principles such as: “I can do all things through Christ which strengtheneth me” (Philippians 4:13).

The immense practical benefits of knowing Greek and plenty of edifying teaching will be included. The class should not be a dry learning of an ancient language, but an interesting, spiritually encouraging, and practical study of the language in which God has given His final revelation. It will help you in everything from preaching and teaching in Christ’s church to answering people’s objections in evangelism house to house to understanding God’s Word better in your personal and family time with the Lord.

What Textbooks Will I Use in Introductory NT Greek?

Required class textbooks are:

1.) Greek New Testament Textus Receptus (Trinitarian Bible Society), the Greek NT underneath the Authorized, King James Version:

alternatively, the Greek New Testament Textus Receptus and Hebrew Old Testament bound together (Trinitarian Bible Society):

2.) William D. Mounce, Basics of Biblical Greek Grammar, ed. Verlyn D. Verbrugge, Third Edition. (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2009) (Later editions of Mounce are also fine, but please do not use the first or second edition.)

4th edition:

3.) William D. Mounce, Basics of Biblical Greek (Workbook), ed. Verlyn D. Verbrugge, Third Edition. (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2009)

4th edition:

4.) T. Michael W. Halcomb, Speak Koine Greek: A Conversational Phrasebook (Wilmore, KY: GlossaHouse, 2014)

4.) T. Michael W. Halcomb, 800 Words and Images: A New Testament Greek Vocabulary Builder (Wilmore, KY: GlossaHouse, 2013)

Recommended texts include:

5.) Danker, Frederick William (ed.), A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and other Early Christian Literature, 3rd. ed. (BDAG), Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2000

6.) The Morphology of Biblical Greek, by William D. Mounce. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing Company, 1994

(Note: Links to Amazon are affiliate links. To save money on buying books on the Internet, please visit here.)

We are using Speak Koiné Greek as a supplement to Mounce because studies of how people learn languages indicate that the more senses one uses the better one learns a language. Speaking and thinking in Greek will help you learn to read the NT in Greek. We are using Halcomb’s 800 Words and Images because learning Greek vocabulary with pictures and drawings helps to retain words in your memory (think about how children learn words from picture books). Mounce is a very well-written and user-friendly textbook, and Halcomb’s works will make the material even more user-friendly.

What Qualifications Does the Professor Have to Teach Greek?

I have taught Greek from the introductory through the graduate and post-graduate levels for a significant number of years. I have read the New Testament from cover to cover in Greek numbers of times and continue to read my Greek NT through regularly. I can sight-read most of the New Testament. I am currently reading the Septuagint through as well. I have also read cover to cover and taught advanced Greek grammars. While having extensive knowledge of Koine Greek, students of mine have also thought my teaching was accessible and comprehensible. More about my background is online here.

My doctrinal position is that of an independent Baptist separatist, for that is what is taught in Scripture. Because Scripture teaches its own perfect inspiration and preservation, I also believe both doctrines, which necessarily leads to the belief that God has preserved His Word in the Greek Textus Receptus from which we get the English King James Version, rather than in the modern critical Greek text (Nestle-Aland, United Bible Societies).

What Do I Need to Get Started?

You will need a computer or other electronic device over which you can communicate. We can help you set up Zoom on your computer in case you need assistance with that.

The class should begin in early February and end around the beginning of June. The class will count as a 4 credit college course. Taking the class for credit is $175 per credit hour. The class can be audited for $100 per credit hour. Auditors will not take tests or be able to interact with the class. Taking it for credit is, therefore, likely preferable for the large majority of people. When signing up, please include something written from your pastor stating the church of which you are a member and his approval for your taking the class. Students with clear needs who live outside of North America and Europe in less well-developed countries in Africa or Asia (for example) may qualify for a discount on the course price. One or two students located in any part of the world who are able and willing to help with video editing also would qualify for a course discount.

For any further questions, please use the contact form here.

Lord willing, I will be starting a 1st year Hebrew class for distance students soon as well. Please also let me know if you are interested in taking that.

–TDR

Yes and Then No, the Bible with Mark Ward (part two)

Earlier this week, I wrote part one concerning two separate videos posted by Mark Ward. The second one I saw first, and since my name was mentioned, I answered. He cherry-picks quotes without context. Ward made what he thought was a good argument against the Textus Receptus.

In part one, I said “yes” to his assessment of IFB preaching. I didn’t agree, as he concluded, that a correction to preaching was the biggest step for IFB. A distorted gospel, I believe, is of greater import, something unmentioned by Ward.

NO

Bob Jones Seminary (BJU) invited Ward to teach on problems with the Textus Receptus (received text, TR), the Greek text behind the New Testament (NT) of the King James Version (KJV) and all the other Reformation Era English versions. It was also the basis for all the other language versions of the Bible. There is only one Bible, and subsequent to the invention of the printing press, we know the TR was the Bible of true believers for four centuries. Unless the Bible can change, it’s still the Bible.

Ward accepted the invitation from BJU, despite his own commitment against arguing textual criticism with anyone who disagrees with him. For him to debate, his opposition must agree with his innovative, non-historical or exegetical application of 1 Corinthians 14:9. It’s the only presupposition that I have heard Ward claim from scripture on this issue.

Critical text supporters, a new and totally different approach to the Bible in all of history, oppose scriptural presuppositions. They require sola scientia to determine the Bible. Modern textual criticism, what is all of textual criticism even though men like Ward attempt to reconstruct what believing men did from 1500 to 1800, arose with modernism. Everything must subject itself to human reason, including the Bible.

In his lecture, Ward used F. H. A. Scrivener to argue against Scrivener’s New Testament, giving the former an alias Henry Ambrose, his two middle names, to argue against Scrivener himself. It is an obvious sort of mockery of those who use the NT, assuming they don’t know history. The idea behind it is that Scrivener didn’t even like his Greek NT.

What did Scrivener do? He collated the Greek text behind the KJV NT from TR editions, and then printed the text underlying the NT of the KJV. It was an academic exercise for him, not one out of love for the TR. Scrivener was on the committee to produce the Revised Version.

The Greek Words of the New Testament

Did the words of that New Testament exist before Scrivener’s NT? Yes. Very often (and you can google it with my name to find out) I’ll say, “Men translated from something.” For centuries, they did.

The words of Scrivener were available in print before Scrivener. Scrivener knew this too, as the differences between the various TR editions are listed in the Scrivener’s Annotated New Testament, a leather bound one of which I own. Ward says there are massive numbers of differences between the TR editions. That’s not true.

Like Ward’s pitting Scrivener on Scrivener and the KJV translators against the KJV translation, claiming massive variants between TR editions is but a rhetorical device to propagandize listeners. The device entertains supporters, but I can’t see it persuading anyone new. It’s insulting.

When you compare Sinaiticus with Vaticanus, there you see massive differences, enough that Dean Burgon wrote, “It is in fact easier to find two consecutive verses in which these two MSS differ the one from the other, than two consecutive verses in which they entirely agree.” There are over 3,000 variations between the two main critical manuscripts in the gospels alone. That is a massive amount. Moslem Koran apologists enjoy these critical text materials to attack the authority of the Bible. It is their favorite apologetic device, what I heard from every Moslem I confront at a door in evangelism.

There are 190 differences between Beza 1598 and Scrivener’s. Scrivener’s is essentially Beza 1598. Many of those variations are spelling, accents, and breathing marks. As a preemptive shot, I know that all those fit into an application of jots and tittles. We know that, but we also know where the text of the King James Version came from and we know that text was available for centuries. God preserved that text of the NT. Believers received it and used it.

Men Translated from Something

When you read John Owen, what Greek text was he reading? He had one. Ward says there wasn’t a text until Scrivener. Wrong. What text did John Gill use? What text did Jonathan Edwards use? They relied on an original language text. What text did John Flavel and Stephen Charnock use? They all used a Greek text of the New Testament.

16th through 19th century Bible preachers and scholars refer to their Greek New Testament. Matthew Henry when writing commentary on the New Testament refers to a printed Greek New Testament. He also writes concerning those leaving out 1 John 5:7: “Some may be so faulty, as I have an old printed Greek Testament so full of errata, that one would think no critic would establish a various lection thereupon.”

The Greek words of the New Testament were available. Saints believed they had them and they were the TR. This reverse engineering, accusation of Ruckmanism, is disinformation by Ward and others.

The Assessment of Scrivener and the Which TR Question

Ward uses the assessment of Scrivener and the preface of the KJV translators as support for continued changes of the Greek text. This is disingenuous. The translators did not argue anywhere in the preface for an update of the underlying text. They said the translation, not the text, could be updated. That argument does not fit in a session on the Greek text, except to fool the ignorant.

Just because Scrivener collated the Greek words behind the KJV doesn’t mean that he becomes the authority on the doctrine of preservation any more than the translators of the KJV. It grasps at straws. I haven’t heard Scrivener used as a source of support for the Textus Receptus any time ever. I don’t quote him. If there is a critique, it should be on whether Scrivener’s text does represent the underlying text of the KJV, and if it does, it serves its purpose.

I have written on the “Which TR question” already many times, the most used argument by those in the debate for the critical text. It’s also a reason why we didn’t answer that question in our book, Thou Shalt Keep Them. If we addressed it, that would have been all anyone talked about. We say, deal with the passages on preservation first. We get our position from scripture.

I digress for one moment. Ward talks and acts as if no one has heard, which TR, and no one has ever answered it. Not only has that question been answered many times, but Ward himself has been answered. He said only Peter Van Kleeck had answered, which he did with a paper available online. Vincent Krivda did also.

The position I and others take isn’t that God would preserve His Words in Scrivener’s. The position is that all the Words are preserved and available to every generation of Christian. That’s why we support the Textus Receptus.

Ward never explains why men point to Scrivener’s. I have answered that question many times, but he doesn’t state the answer. He stated only the position of Peter Van Kleeck, because he had a clever comeback concerning sanctification. But even that misrepresented what Van Kleeck wrote.

The position I take, which fits also the position of John Owen, I call the canonicity argument. I have a whole chapter in TSKT on that argument. I’ve written about it many times here, going back almost two decades.

If pinned to the wall, and I must answer which TR edition, I say Scrivener’s, but it doesn’t even relate to my belief on the doctrine. What I believe is that all of God’s Words in the language in which they were written have been available to every generation of believer. I don’t argue that they were all available in one manuscript (hand-written copy) that made its way down through history. The Bible doesn’t promise that.

Scriptural Presuppositions or Not?

The critical text position, that Ward takes, cannot be defended from scripture. The position that I take arises from what scripture teaches. It’s the same position as believed by the authors of the Westminster Confession, London Baptist Confession, and every other confession. That is accepted and promoted by those in his associations.

Ward doesn’t even believe the historical doctrine of preservation. Textual variations sunk that for him, much like it did Bart Ehrman. Ward changed his presupposition not based upon scripture, but based upon what he thought he could see. It isn’t by faith that he understands this issue.

Some news out of Ward’s speech is that he doesn’t believe that God preserved every word of the Bible. He says he believes the “preponderance of the manuscripts” view. I call it “the buried text view.” Supporters speculate the exact text exists somewhere, a major reason why Daniel Wallace continues looking. That is not preservation.

“The manuscripts” are an ambiguous, sort of chimera to their supporters. They don’t think they have them yet, so how could there be the preponderance of anything yet? That view, the one supported by two books by BJU authors, From the Mind of God to the Mind of Man and God’s Word in Our Hands, they themselves do not believe. Ward walked it back during his speech too. They don’t really believe it. It’s a hypothetical to them. Men of the two above books don’t believe at least that they possess the Hebrew words of 1 Samuel 13:1 in any existing manuscript. At present, like a Ruckmanite, they correct the Hebrew text with a Greek translation.

In the comment section of the above first video, Ward counsels someone in the comment section to use a modern translation from the TR, such the NKJV. The NKJV, Ward knows, doesn’t come from the TR. There are variations from the TR used in the NKJV, a concession that Ward made in a post in his comment section after being shown 20-25 examples. He wrote this:

First the concession: I am compelled to acknowledge that the NKJV does not use “*precisely* the same Greek New Testament” text as the one underlying the KJV NT.

He could not find 2 John 1:7 of the NKJV in any TR edition. Does it matter? It does, especially a translation that calls itself the NEW King James Version. The translators did not use the same text as the KJV used, however Ward wants to represent that. I would happily debate him on the subject. I’m sure Thomas Ross would.

Mark Ward has committed not to debate on the text behind the KJV. He is committed now to taking shots from afar, leaving the safe shores of vernacular translation to hit on the text. Even though he says the variations do not affect the message of the Bible, he continues to argue against the text behind the King James Version.

John 3:36, the Second “Believeth” (Apeitheo), and English Translation of the Bible

The King James Version (KJV) of John 3:36 reads:

He that believeth on the Son hath everlasting life: and he that believeth not the Son shall not see life; but the wrath of God abideth on him.

Whoever believes in the Son has eternal life; whoever does not obey the Son shall not see life, but the wrath of God remains on him.

(1) in relation to God disobey, be disobedient (RO 11.30); (2) of the most severe form of disobedience, in relation to the gospel message disbelieve, refuse to believe, be an unbeliever.

not to allow oneself to be persuaded; not to comply with; a. to refuse or withhold belief

An Orthodox View of Our English Bibles? Considering Fred Butler’s KJVO Book and the Doctrine of Preservation

Whenever I read the word, “Bibles,” I get a bit of a chill down my spine. Which Bible is the right Bible if there are plural Bibles, not singular Bible? Isn’t there just one? Why are we still producing more and different Bibles? How many are there? What I’m describing is the biggest issue today with translations, not the King James Version, but now it gets little to no coverage compared to other so-called problems.

Many anti-KJVO books have been written, most often, and this continues to be the case with Butler’s book, calling KJVO (King James Version Onlyism) “dangerous.” It’s true that many KJV Onlyists do not believe a scriptural bibliology. I would contend that most are sound, but it’s true also that many are not. That would be a worthwhile criticism of KJVO, confronting those who do not believe in the preservation of scripture, who do not believe God preserved His Words in the original languages, apparently necessitating God’s correction of them in an English translation. This happens to be the same doctrinal position as Fred Butler. He just deals with the consequences of that belief in a different way.

I don’t know how “dangerous” it is to believe in a single Bible of which translation for English speaking people is the King James Version. How will that get someone in trouble? What’s the danger? Even though Butler calls the position dangerous, he doesn’t explain why anywhere in his book, which I find is most often the case with books of this kind. In general, KJVO take the general position that there is only one Bible, which there is. That is a biblical, logical, and historical position: one Bible. Several Bibles is not.

In his preface, recounting his own personal journey away from the King James Version, Butler says,

I found myself helping them [speaking of others also departing] think critically through KJVO argumentation, as well as develop an orthodox view of our English Bibles.

Why and how is it orthodox to refer to the Bible in the plural, “Bibles”? Again, there is only one Bible, and historically Christians have believed in only one. Some type of multiple-versionism, I believe, creates far more confusion and danger. Usually orthodoxy refers to doctrine. Is the doctrine behind multiple versions and textual criticism orthodox? It’s popular today, but not orthodox.

I’m not going to debunk most of the arguments of Butler’s book. His book is exploring zero new territory others cover much more than he. He mainly addresses KJVO advocates of either double inspiration or English preservationism, very low hanging fruit. He barely to if-at-all distinguishes one view from another. He lumps Peter Ruckman and Gail Riplinger with Edward Hills, D. A. Waite, and David Cloud. He uses a very broad brush. I would not anticipate his persuading one person to his position.

One unique argument I had never read was that KJVO are not Calvinist. The idea here is that if you’re not a Calvinist, then you must be wrong in this position on the Bible. The biggest movement of those who exclusively use the KJV as an English translation are Calvinists. The Westminster Confession and London Baptist Confession, as well as many of these Calvinist confessions, hold to the perfect preservation of scripture, which is a one Bible position.

An orthodox view should be a scriptural view. Butler doesn’t establish any kind of biblical and historical view of the preservation of scripture. Butler writes this:

It is true God calls us to have faith, but our faith is grounded upon objective truth.

What is objective truth? Is textual criticism objective truth? No way, and he doesn’t make that connection. It can’t be made. Scripture is the truth on which bibliological positions stand. Butler takes the view agreed by modern evangelicalism, not based upon scripture. He has not faced a bit of criticism from the evangelicals who interview him. He should sit down for a talk with someone who does not take his position to see how his arguments will stand up.

Most people who use the King James believe that it is an accurate translation of a preserved original language text. Obviously, the King James Version itself has changed since 1611. KJV supporters know that. This indicates that they believe that the preservation of scripture occurs in the Hebrew and Greek text. Butler writes:

The Bible never claims God’s Word is only found in one translation. KJV onlyism is unsupported by the Bible itself.

Maybe that confronts Ruckmanism, but I’ve never heard a single person attempt to defend single-translationism from the Bible. The French, Spanish, Russian, etc. can all have a translation from the same text as the King James Version. Butler knows this, but he makes this claim anyway, and it’s a strawman. It doesn’t help anyone. More than anything it gives fresh meat to evangelical friends in an evangelical bubble. On the other hand, he never lays out what the Bible does claim.

There are varied views on preservation among evangelicals. I don’t know of one modern version supporter, who believes in perfect preservation of scripture. Daniel Wallace doesn’t believe scripture teaches the preservation of scripture and he has many supporters. That is now a very common view. He believes in the preservation of the Word, but not the Words. Butler takes a view that might be the most common for evangelicals. Most evangelicals in the pew don’t know this position, but perhaps the majority of conservative evangelical leaders take the position Butler describes:

Yes, I believe God preserves His Word, but I believe it is in the totality of all the available manuscript evidence, variants and copyist errors included.

Try to find that in historical bibliological literature. You won’t find it. It really is a reactionary position to textual criticism among evangelicals. It isn’t a biblical position. Nowhere does the Bible teach it. It’s very much like what you might read on creation today. Confronted with science, professing Christians invent a day age theory for old earth creationism.

Almost all of what Butler finds are theologians, often unbelieving ones, willing to admit that there are copyist errors, which produce textual variants. He and others act like KJVO don’t know that or don’t believe it happened. The history of God’s preservation of scripture is not the same parchment and ink making its way down through time in a pristine condition. God preserved His Words. This physical copy view is not taught in the Bible and it’s only made up as a straw man to create a faux argument.

When you read Butler’s view in his above quote, look carefully at what he says. First, he says God preserves His Word, not God preserved, completed action, like Jesus said, “It is written,” in the perfect tense. He doesn’t say “Words,” because He would never say that. It’s God’s Word in a very ambiguous sense. Jesus said, my words shall not pass away (Matthew 24:35). Where does the Bible or even history present this “totality of available manuscript evidence” position?

For Butler the text isn’t settled, like the Bible speaks about itself. He doesn’t know what the Words are. He doesn’t know all of the ones by which He is to live by. I would contend he doesn’t even believe the position he espouses. How would he account for new evidence, which is still coming? What does he do with a passage like 1 Samuel 13:1? I’ve never read an evangelical, who takes his position, who believes that we possess a manuscript with the very words of that verse.

What motivated me to write this post was one aspect of Butler’s book and that is his attack on the teaching of preservation in scripture. Among everything that he writes, I want to deal only with Psalm 12:6-7, mainly to show how men like him deal with these preservation texts. He writes:

The one passage that nearly all KJVO advocates use for establishing the promise argument is Psalm 12:6,7. . . . The immediate antecedent for the plural pronoun them is the plural pronoun, words. Thus, it would seem to make sense that we can conclude God has promised to preserve His words in a physical text.

The Hebrew language, however, is sharply different from English in that it has grammatical gender, something not common to English. In Hebrew, the pronouns will match the antecedent nouns in both number and gender. Here in Psalm 12:6, 7, the two thems of verse 7 are masculine in gender and with the second them being singular.

The closest antecedents in our English translation, the two nouns words found in verse 6, are feminine, so they do not match the masculine thems.

Butler goes on to say that “them” refers to the poor and needy back in verse 5 because they’re feminine. Butler’s argument here has been thoroughly debunked. He’s wrong. First, however, there are many verses in the Bible that teach the perfect preservation of every Word of God. Psalm 12:6, 7 are two of many. There is a great chapter on these verses by Thomas Strouse in Thou Shalt Keep Them, our book on the preservation of scripture. I’ve also written a lot on it (here, here, and here).

Here’s the short of it. Repeatedly in the Old Testament, and as a part of Hebrew grammar, a masculine pronoun refers to a feminine Word of God. You see it again and again in Psalm 119, the psalm entirely about the Word of God (verses 111, 129, 152, 167). There are many other examples. You can find this very rule in Gesenius’s Hebrew grammar, which I used in second year Hebrew in graduate school.

The number argument doesn’t work either, which is why the KJV translators translated the pronoun, “them,” the second time. That’s also Hebrew grammar. It is very common after a plural pronoun for a singular to follow in order to particularize every individual in the group. A collective plural is suggested by the singular. This is also why the NKJV translators, who are not KJVO, translated it “them.”

The Hebrew grammar says just the opposite of what Butler writes. Critical text and modern version men continue to trot out this argument, when they should well know that it’s been answered many times. I’ve never had one of them attempt to deal with it, because it is irrefutable. It’s why many, many preachers and theologians through the centuries, including Jewish scholars, have said that “them” in verse seven refers to God’s “words” in verse six. The gender disagreement argument is a moot point. Without gender, the rule reverts back to proximity, and “words” is the closest antecedent to “them.”

Either Butler didn’t know the gender disagreement argument or he assumed that his readers wouldn’t know any better. Knowing the Hebrew grammar and reading what he wrote, it reads like he was just borrowing from the writings of other people. I’ve read this argument from Douglas Kutilek online. He’s been confronted with the Hebrew grammar and he’s never answered me or anyone else on it. He does not know what he’s talking about.

So much more could be said in review of Fred Butler’s book, but rest assured that God has preserved every one of His Words in the language in which He inspired them, and made them available for every generation of believers. The King James Version is an accurate translation of those Words.

The Required Rejection of Dismayal

The English, “dismayed,” is found only in the Old Testament, and 31 times in the King James Version. The Hebrew word is hay’tawt (my transliteration), which is found 57 times in the Old Testament, the following the first five usages:

Deuteronomy 1:21, “Behold, the LORD thy God hath set the land before thee: go up and possess it, as the LORD God of thy fathers hath said unto thee; fear not, neither be discouraged.”

Deuteronomy 31:8, “And the LORD, he it is that doth go before thee; he will be with thee, he will not fail thee, neither forsake thee: fear not, neither be dismayed.”Joshua 1:9, “Have not I commanded thee? Be strong and of a good courage; be not afraid, neither be thou dismayed: for the LORD thy God is with thee whithersoever thou goest.”Joshua 8:1, “And the LORD said unto Joshua, Fear not, neither be thou dismayed: take all the people of war with thee, and arise, go up to Ai: see, I have given into thy hand the king of Ai, and his people, and his city, and his land.”Joshua 10:25, “And Joshua said unto them, Fear not, nor be dismayed, be strong and of good courage: for thus shall the LORD do to all your enemies against whom ye fight.”

The Knowledge which the Saints have of God’s Beauty and Glory in this World, and those holy Affections that arise from it, are of the same Nature and Kind with what the Saints are the Subjects of in Heaven, differing only in Degree and Circumstances. . . . Those Affections that are truly Holy, are primarily founded on the Loveliness of the moral Excellency of divine Things. Or, (to express it otherwise) a Love to divine Things for the Beauty and Sweetness of their moral Excellency, is the first Beginning and Spring of all holy Affections. . . . That Religion which God requires, and will accept, don’t consist in weak, dull and lifeless Wouldings, raising us but a little above a State of Indifference: God, in his Word, greatly insists upon it, that we be in good Earnest, fervent is Spirit, and our Hearts vigorously engaged in Religion.

Recent Comments