Home » Search results for 'king james version' (Page 2)

Search Results for: king james version

The Engagement of Others on the Modern Versions or King James Version

For the Apostle Paul to leave Judaism for faith in Christ, he had to count his old religion as dung. Paul’s life and lifestyle was woven into Judaism. It was a major break to say he had been wrong and now he was going an opposite direction and taking a different position. Today you don’t see that much.I’m confronted with the consideration of wholesale change every time I evangelize in the San Francisco Bay Area. I sat in the living room two days ago and talked to a Hindu man from Nepal, who had been in the United States for two years. We talked for about an hour and he was about 75% sure on his English. It would take awhile to get across everything he needed to know to leave his family religion. This kind of situation is more common than ever in the United States, where a person is further away from sufficient salvation knowledge, including for multi-generation Americans.I grew up in a home where my parents were saved when I was a toddler, so I grew up in a Christian home. In one sense, my parents, sister, brother, and I grew up as a family. However, since I’ve been saved, even since I’ve been a pastor, I have made changes in beliefs and practices, and so has our church. I would say 5 to 10 pretty major changes, that really affect our lives personally and drastically. If the Bible is the sole authority for faith and practice, Christian growth means a willingness to change when you see something in the Word of God.I haven’t noticed that most men and churches are willing to change, unless it is a leftist direction or someone might say, downward direction. It’s easier to get more loose or become more like the world, and that’s happening. People are sliding to the left or downward. It’s easy to see that churches are changing. It’s not a reaction to the Word of God, which means it doesn’t fit with the historical positions and practices of Christianity.Mark Ward wants churches that use the King James Version to change, and he has just written another post encouraging them instead to start using a modern version, which was published by The Gospel Coalition, an organization from the left of evangelicalism. Each new post seems to go a little further than the last. The last time he challenged fundamentalists to separate from churches and leaders that use the King James Version only (KJVO), based upon their disobedience to 1 Corinthians 14. In this very latest, in a translation to the gospel coalition crowd, Mark adds both that “KJV-onlyism is not a Christian liberty issue” and that it “makes void the Word of God by human tradition.” He implies KJVO are weaker brothers, whose consciences are bound by extra or unscriptural scruples. He didn’t challenge The Gospel Coalition to separate from KJVO like he did the fundamentalists.To change, it is true that I would need to be convinced by scripture and this is something, it seems, that Ward maybe notices about his target audience. However, would Mark Ward be willing to change based upon the teaching of the Bible? I and my church use the King James, based upon scriptural presuppositions. I am not convinced that Mark takes his position based on scriptural presuppositions, but he’s arguing like this is important. This is new for modern version proponents. They didn’t come to their position from scripture and yet here Mark Ward is using scripture to persuade textus receptus proponents to use a modern version. I want to stay on that track.Some commented on Ward’s essay. They discussed how to persuade a King James Only person. One wrote:

Often they have strong built-in assumptions, and if you can ask them some good questions, and thereby pull out a few of the key pieces in their house of cards, it will crumble. I like to ask (if the conversation seems to be headed a direction where this question is helpful) “Which Textus Receptus edition do you believe is the perfect one? The answer might be ‘I didn’t know there was more than one?’ or ‘I guess the one that the KJV is based on’ and either of these responses can lead to the collapse of the house of cards.

We believe that the Holy Bible as originally written was verbally inspired and product of Spirit-controlled men, as well is Divinely preserved in the same fashion, and therefore, has truth without any mixture of error for its matter.

By “in the same fashion,” we are saying “as originally written” and “verbally.” It’s a short statement for a website, and we have a longer one, but we say something about preservation.If I were going to ask questions about this issue, the house of cards would start falling for me, if someone couldn’t provide some kind of systematic scriptural basis for his position. I could ask a lot of questions like that, which people cannot answer. Sometimes they will not answer. Most of the time, I’ve found that they don’t care. They do. not. care. that their position has never been buttressed by scripture and especially that it didn’t start that way. It actually goes further. Most of them are annoyed when I ask, and they want to end the conversation, because bringing up appropriate scripture on the subject is an unacceptable inclusion into the discussion. The Bible triggers them.So. What is important to me is a scriptural doctrine of preservation. The doctrine must also must be historical. If it is new, it better be very, very persuasive from scripture. It should be both, but if it isn’t historical, the scriptural part ought to do away with the old, wrong position. That’s how change happens, don’t you think? I don’t separate over the use of the modern version. God promised to preserve His Word. I believe God. I don’t want someone to imply God is a liar. I don’t want people to doubt what He said. I want to guard the doctrine of preservation. It’s the wrong doctrine over which I separate. Evangelicals and fundamentalists are changing the doctrine of preservation without a scriptural basis, mainly by just leaving it out. To tell you what I really think, I believe they are dishonest in just leaving it out. It’s like Mormons leaving out the part about the special underwear.I have a difficult time, I must admit, believing that someone, who never started with a scriptural or historical position on the preservation of scripture, wants me to change my position based on scripture. He’s got a lotta lotta work to do. A lotta. He can show up on multiple podcasts, in exciting and noticeable varied other media, and before Trump-like stadiums of people and it won’t start a ripple of change on the surface of my pond. He’s using the wrong or faulty pebbles.

Analyzing King James Version Revision or Update Arguments, pt. 2

I’m happy our church uses the King James Version. Because of our belief in the preservation of its underlying text, our church can’t use the New King James Version, even if it were a superior translation. The NKJV doesn’t come from the identical Hebrew and Greek text of the KJV, so we won’t use it. Should we use one of the other revisions or updates of the King James Version? I’ve written that we have several reasons for continuing to use the King James Version that far outweigh the difficulty of some outdated words. Those can be explained. If you want, you can buy a Defined King James Version, which defines those words in the margins (which is why it is called “Defined”).

Here’s what we see happen. Someone says words in the King James Version can’t be understood. We say, there is a Defined King James Version, if you want it. The person says words in the King James Version can’t be understood. We say, there is a Defined King James Version, and it defines those words. Crickets. What are we to think about that? I think a sensible inclination is to think that he doesn’t really care whether they can understand the King James Version or not. He doesn’t like or want the King James Version.

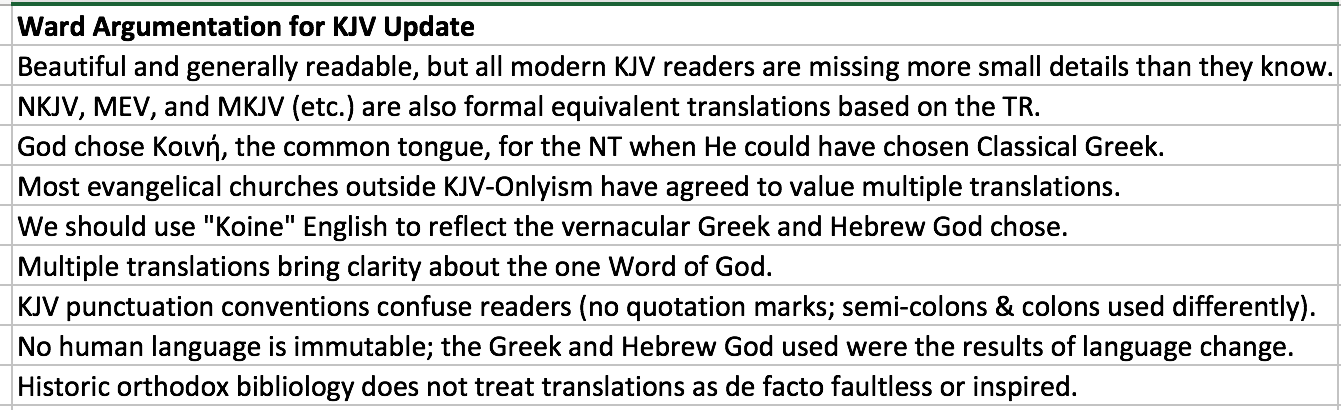

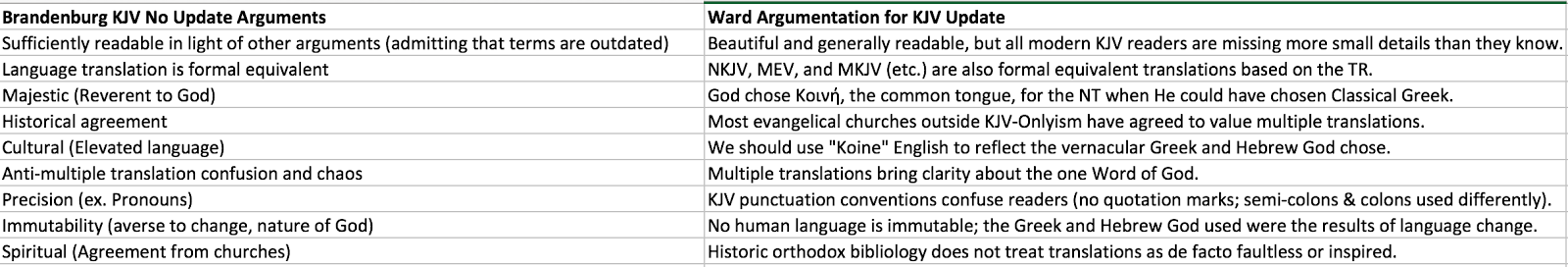

This post will continue dealing with arguments against the support of the use of the King James Version. I’ve written that Mark Ward really gave one argument, that is, updating outdated words. We’ve answered that charge in a number of different ways. We had several arguments against a revision that Ward gave to dispute our reasons. They weren’t arguments. They were attempts at answering our arguments, and I’m going to continue to answer what he wrote in his chart I posted in part one. I’m going to keep using the *asterisks to mark a new argument, and I’m to the fifth of nine.

*How low can you go with language? The King James Version translates in a formal equivalent of the Hebrew and Greek text received by the churches, the words preserved and available to every generation of church. It stays there with formal equivalence in translation language. It gives us God’s Word, and it is God’s Word, so it is respectful to God. People have loved the King James because it reads like God’s Word, not like a comic book or a popular novel. That might be what some people want, but church leaders shouldn’t take that bait. This is what we see in our culture and it spreads to churches. There is a tremendous lack of respect and reverence to our culture and instead of turning the world upside down, churches are being turned upside down. We shouldn’t cooperate with that as a church.

*Ward has expressed numerous times that he is concerned about how that the translation of the King James will hinder evangelizing the “bus kid.” I evangelize every week numerous times. A week doesn’t go by where I will not preach the gospel to someone. I’m not talking about in our assembly during a service, when I preach there. I’m talking about out in the world. When it comes to the translation issue, the greatest hindrance for evangelism is the translation confusion and chaos out there. People have less trust in the Word of God. Offering more and more “translations” takes away confidence in scripture. More and more translations published gives the impression that the Bible is malleable in the hands of men. It takes away respect. I think everyone knows that.

Ward says more translations will bring clarity. I get the argument. He’s saying that you can lay out twenty translations in front of you and compare what the translators did to attempt to get what a passage is saying, using them like a commentary. Translations shouldn’t be commentaries. They aren’t crafts for men to read in their theology or maybe even a pet peeve. What you very often get today are men that do translation shopping, where they find a translation that agrees with their position, and they keep looking until they find it. It puts men in a position of sovereignty over God’s Word.

*For the next argument, Ward says the KJV is not precise because it has confusing punctuation that people today are not accustomed too. My original point is that you can read the number in second person personal pronouns in the King James Version, and you can’t in modern versions. You see those communicated in the original language and you do in the King James Version. You don’t read in the modern versions the specificity of the original languages. You get the same kind of precision in the verbs of King James: singular, I think, thou thinkest, and he thinketh, then plural, we think, you think, and they think.

The King James does more than what I just described in precision. Look at the following examples of Matthew 3:13:

King James: “Then cometh Jesus from Galilee to Jordan unto John, to be baptized of him.”

English Standard: “Then Jesus came from Galilee to the Jordan to John, to be baptized by him.”

New American Standard: “Then Jesus arrived from Galilee at the Jordan coming to John, to be baptized by him.”

New King James: “Then Jesus came from Galilee to John at the Jordan to be baptized by him.”

“Cometh” is present tense in the original language, and yet the modern versions translate it as past or aorist. It’s also present tense in the critical text, and yet the modern translators, all of these three very commonly used, give it a past tense, which is not accurate.

*God is immutable. God’s Word should not be so apt to change. Just because new translations are made and can be made, we should not be quick to change God’s Word. Keeping a standard and us changing to fit that standard is more in fitting with a biblical way of life, than to keep adapting the Bible to us. That was my point.

There are reasons why you could mark a church by what version of the Bible it used. The translation issue reflected a new-evangelical church. The new-evangelical church changed Bibles. This has been the nature of pragmatism and regular change in churches. Churches have a tradition and keep a culture stable with a tradition. When churches change and change and change, it’s no wonder we can’t keep the slide from happening. Translation change got this going with churches. This is a historical reality.

The language of the Bible is still the language of the Bible. No one should be advocating change of that. However, the actual language of the Bible has become out of reach of a degrading culture. We should not pull the Bible down with it. It is an anchor for a culture. When I say that, I’m not talking about a discussion of the use of the English word “halt,” but of Hebrew poetry and long Greek sentences and metaphors used by the authors that are no longer in use.

Language itself, it is true, isn’t immutable. However, God’s Word is immutable, even when language is changing. We want people to conform to what God has done, rather than encourage an expectation of the Bible adapting to people.

*The last argument is the one that I see Mark Ward understand the least. The King James Version was accepted by the churches. It was used and continued to be used by the churches. The church is the pillar and ground of the truth. Jesus gave the church the truth. The church is the depository of the truth. The new translations aren’t being authorized by churches, but by independent agencies and with varied motivations. Churches keep the translation issue on a spiritual plane, instead of other incentives, like profit, business or trade, and intellectual or academic pride.

The modern versions did not originate from churches. They started among textual critics, who were almost unanimously unbelieving. This wasn’t a movement of churches, but of extra-scriptural, parachurch organizations. College and universities, which were laboratories of liberalism and upheaval, is where the modern version movement began. This is not how God has done and does His work. He uses the church.

The biblical and historical doctrine of preservation leads our church to use the King James Version, because of its underlying original language text. Other thoughtful reasons motivate our church with the translation of the King James. We have considered an update and we are not supportive for reasons we gave. We have careful and reasonable arguments that outweigh arguments against. There is no groundswell of support for an update or revision of the King James Version from churches that use the King James Version.

Analyzing King James Version Revision or Update Arguments, pt. 1

In the last month, I have written two posts about contemporary usage and support of the King James Version of the Bible, the first differentiating my biblical position from an untenable King James Version position and the second explaining why an update wouldn’t occur. Both of these posts resulted, as is often the case, in discussions about the English translation of the Bible with sharp disagreements and heated debate. I had written the second post because of comments on the first.

I have noticed a new trend in opposition to the King James Version. If you won’t support an update of the King James Version, then you are at the least insincere and at the most lying about your TR-only position, one which rests on a belief of the superiority of the underlying original language text of the King James Version. I haven’t met one of these critics who even supports the underlying text. In actuality, it is only a line of attack on particular supporters of the King James Version, with the obvious goal of eliminating any remaining endorsement of it, essentially retiring it from public use to a historical artifact.

An obvious question is “what difference does it make to those who don’t use the King James Version whether another church does?” It really doesn’t matter to them. They say it does, but that’s only for its usefulness to mothball the King James. It couldn’t matter to them, because their position is that believers are guaranteed by God only the truth necessary to be saved. That is either the boundary or the core of their teaching, depending on whether they are fundamentalist or evangelical. They also say that the differences between the modern versions and the King James do not change any doctrines. It can’t matter to them.

The saints who believe that they have available to them every Word of God found in the originals are supporters of the King James Version. They are concerned about every Word. You can’t out-concern every Word concern. When people come along, who say they are fine with 7% difference as long as all the doctrines are preserved, they don’t have an argument that relates to having every Word available. You know they are either ignorant or disingenuous, if they say that argument works for them. They are being far more lenient among themselves with acceptation of massive differences even between Sinaiticus and Vaticanus, two manuscripts they call “the best” and “far superior to the textus receptus.” As Dean Burgon wrote in Revision Revised (1883, p. 12): “It is in fact easier to find two consecutive verses in which these two manuscripts differ the one from the other, than two consecutive verses in which they entirely agree.”

If you say you can’t understand what I’ve been writing so far, then you are just playing games. I don’t think playing games is the worst of it. The worst of it is denying the biblical and historical doctrine of preservation and, therefore, not trusting God and what He said He would do. Some will not doubt that He keeps them saved, keeps their soul intact. They do doubt that He kept His Word, so they have modified the doctrine of preservation in a similar fashion that we also see the alteration of inerrancy. It’s no wonder an Andy Stanley is pushing the ejection button on “the Bible tells me so.” We had already seen a similar move from Daniel Wallace, redefining in the 21st century what had already been redefined toward the end of the 19th century, watering down further and further a scriptural and historical bibliology.

Even with the vital importance and truth of everything in this post so far, my point in writing has been to deal with what are said to be reasons to tip supporters of the King James Version to update into contemporary readability. Here is the graphic with Mark Ward’s arguments, really ones addressing the arguments against a KJV update.

It’s difficult to prove the negative, the burden of proof upon Ward. He has to prove people don’t know something that they can in fact know. He knows they can know, but he is asserting here that it is possible that it is more difficult for them to know with the KJV. Someone who wants to know can know, which is the burden in scripture, but Ward is saying that it’s got to be easier to know than it already is.

Ward buttresses his argument with examples like “halt,” the English word found six times in the KJV. No one ever told me what “halt” meant when I was a child, the equivalent of a bus kid in a small rural town, but I still knew without explanation even as a small child. I don’t remember ever not knowing the essence of what “halt” meant. Ward’s argument has been that he had never met anyone who had known what it meant. Ward is using what is called “anecdotal evidence,” which is very often logically fallacious. An example is, “Smoking isn’t harmful, because my grandfather smoked a pack a day and he lived to be 97.” I counter his anecdotal evidence with my anecdotal evidence, the weakness of anecdotal evidence.

Some very good arguments against Ward’s anecdotes were given that he chose not to answer. They show the fallacy of his argument, and his not answering them would bring further doubt to his anecdotes. One of several not answered was offered by Thomas Ross in the comment section:

In Israel, if bus kids can understand a narrative in Genesis but cannot understand exalted Hebrew poetry in the prophets, should a revised version of the OT be created?

To understand any of the poetry of scripture, one is expected to comprehend how Hebrew poetry functions. Ward thinks “bus kids” must understand a translation for it to be within the vernacular, a requirement to his argument. The question here is whether Hebrew poetry is within the range of a “bus kid.” I could add many corollaries to Ross’s argument, including the understanding of Hebrew weights and measures.

*Answers to his first argument could fill several blog posts, but *his second argument says that existing recent translations of the textus receptus, like the KJV, are also formal equivalents. Ward was responding to the argument that language translation is formal equivalence. Formal translations follow the language from which they are translated, which itself isn’t vernacular. Newer translations might also be formal equivalence, but that still means that they provide a reading not in the vernacular. That’s the challenge of the “bus kid.” Even in the MEV (Modern English Version), an updated translation from the received text, you read sentences in Ephesians 1 far past the readability of the modern bus kid. Will the bus kid understand Job 24 in the MEV? If those are a problem, they still exist in a recent formal equivalence. Ephesians 1 and Job 24 continue as language translation, so also continue to belie the dialect of the “bus kid.”

*An argument against an update is the majesty of the King James and reverent language. Ward countered with God using koine and not classical Greek. The Greek of the New Testament is called koine, which means “common.” Koine differs from classical Greek, and Ward is saying that God was saying something to us by using koine, instead of classical. He according to this argument, therefore, was also saying that He wants His translations common.

The idea of koine or common was that written in the Hellenistic period or when Greek was the common language of the world, spread through the conquests of Alexander the Great. Koine was not just the literary language of the New Testament, but also of everything else in that period that was written. At the time it was in use, classical Greek wasn’t “classical.” It was just Greek. Classical Greek was the Greek of a previous historical period that through time became koine through the influences of its circulation. It was the best because it was universal so more people could read it. Greek was not the language of the world in the classical period. Today koine would be English, because it is the common language of the world.

Antonio Jannaris in his An Historical Greek Grammar (pp. 4-5) writes that literary, conversational, and vulgar Greek were used during every period, including the classical; however, that all “literary composition” rose “above daily common talk.” Daniel Wallace at the beginning of his Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics says that New Testament Greek, based on on contemporary writings in the papyri, was not vulgar. Many, many Greek grammarians consider over half of the New Testament to be a literary Greek, including Hebrews, Luke, Acts, James, the pastoral epistles, 1 Peter, and Jude.

Ephesians 1:3-14 forms one sentence and is about 240 words in the English. Right after it, verses 15-21 contain 167 words in the English. 2 Thessalonians 1:3-12 is a long sentence. This is what is meant by “translational English.” Each of these sections in the Greek text is an entire sentence. Do people write or speak that way today? They don’t.

*When I write “historical agreement” as an argument, I mean that through history, churches agreed to use the King James Version. The church is the temple of the Holy Spirit (1 Cor 3:17) and the common faith of believers is the unity of the Spirit (Eph 4:3). This is how the God guided believers to the New Testament canon. There hasn’t been a unifying translation of scripture, where the church found such agreement. For hundreds of years, when pastors said, “open your Bible,” it was the King James Version. The King James was not displaced by the church. It’s been the slow bleed of dozens of pinpricks. Churches like ours will not toss that history away.

Ward says that most evangelical churches have agreed to value multiple translations. That is such an ambiguous statement with almost every word in contention—“most,” “evangelical,” “agreed,” and “value.” We live in a day of theological and cultural diversity that barely agrees. It’s worse than ever. Our churches trace this to the compromise and capitulation of evangelicalism. We repudiate evangelicalism, not follow its lead.

More to Come.

Revising the King James Version and Pleasing Absolutely No One

For the sake of this post, I’m calling people who use the King James Version, those who love the King James Version (TWLTKJV). TWLTKJV aren’t calling for an update of the KJV. The only people I hear call for an update of the KJV are people who don’t like the KJV (PWDLTKJV). The people who want a contemporary translation don’t care about the text translated into the King James Version. They are more concerned about whether people are going to understand what they are reading, rather than the textual issue. If they really wanted something contemporary, that’s already available anyway in numerous translations, including ones from at least a very similar text.

PWDLTKJV challenge TWLTKJV to make a new translation of the KJV. They don’t want a new translation of it. They are fine with the present translation of it. They love it. They aren’t looking for contemporary English. They don’t think it’s a problem. It’s not a reason for either wrong beliefs or wrong practices with their people.

The issue of further modernization of the KJV comes from PWDLTKJV. It’s not that they want a new translation. It’s a trap issue. They want to see if TWLTKJV really do think that the Bible was preserved in the English language and not in the original Hebrew and Greek. They want to see if TWLTKJV really are loyal to a translation and not the very words that God inspired.

TWLTKJV think there is far more to a translation than what is the most understandable. They think there should be some difficulty or reticence to “changing the Bible.” Men shouldn’t be so free to change a translation of God’s Word. It’s a bad precedent. It’s very common today regularly to keep coming out with this and that new translation, update after update, so that God’s Word becomes very fungible. If you don’t like how it says it, you can just change it. The Bible as a standard isn’t something that should change easily.

PWDLTKJV and pressure to change it are those who already want to get people off of the KJV. The NKJV translators for instance didn’t accept the superiority of the TR. They weren’t TR believers. They were new translation people, not people sold on the TR. They decided not even to use the identical text as the KJV and yet still call it the NKJV, which to TWLTKJV seems dishonest. The NKJV translators were free not to use the identical text, but they get angry, I’ve found, when you question them about those changes. They really shouldn’t be able to have it both ways.

PWDLTKJV wouldn’t even use the text behind the KJV to translate into other languages. They would use the critical text. Yet, these are the people who say the KJV needs an update. If they don’t want that text in other languages, then why would they want it in English? They don’t. All the momentum for an update KJV comes from PWDLTKJV.

The nature of scripture as God’s Word is changeless. God is changeless. His Word is changeless. This popularity of changing doesn’t fit the nature of God.

An acceptable modernization of the KJV would and should come from TWLTKJV. It shouldn’t come from people who don’t care. TWLTKJV don’t want an update.

Just for discussion sake, let’s say that TWLTKJV decided they wanted an update in more contemporary language, changing some of the words. The churches would need to agree that they wanted it. I’m talking about the churches of TWLTKJV are the ones to change it. The church is the pillar and ground of the truth and it is from the church, the church of TWLTKJV that should spearhead the update. If they don’t want to do it, why should it be done? They accept the KJV. They aren’t people, like PWDLTKJV who want to keep changing and changing and changing and updating and updating God’s Word, like so much silly putty.

An update is not going to be done on the momentum of PWDLTKJV. In the end, TWLTKJV will not be pleased by an update. They don’t want it. They believe there are many good reasons not to change the KJV, ones that outweigh, even far outweigh those for changing. PWDLTKJV will not be pleased with an update, because they aren’t going to use the update either. They don’t care. This is why the update isn’t going to happen with the momentum, really fake momentum, of PWDLTKJV. It’s just an issue to be used, like propaganda, against TWLTKJV by PWDLTKJV. I don’t think they even expect TWLTKJV to change. It’s just another reason to keep mocking them, like the mainstream media mocks Republicans for similar superficial and propaganda-like reasons.

A better use of everyone’s time, exponentially more important than pushing for an update of the KJV, is to dig into what the Bible says about it’s own preservation and to study what God’s people have believed about the preservation of scripture. Everyone should get settled what scripture says about its own preservation and about the settled nature of scripture. If men won’t settle on what they believe about preservation, they aren’t going to get the issue of the text or the translation right anyway, and I don’t trust them. No one should.

In the discussion we had here a few weeks back on the King James Version, Thomas Ross in the comment section made a good point that the Hebrews, the Jews, over millennia didn’t suggest for an update of the Old Testament Hebrew text to make it more modern. Men should consider why changing the Word of God is not an option. I understand the issue of a translation isn’t identical. However, it is at least a similar issue. The very Words matter. The text is a settled standard. It shouldn’t be updated, just like there isn’t a call for the updating of the language of the U.S. Constitution, but even less so for scripture. Men should just study and explain the Bible, rather than talking constantly about updating.

The sacred nature of scripture should preclude it from so many changes. It undermines trust in the Bible. It turns the authority of God’s Word upside down, subordinating it to the whims of men.

************

Added after comment 66 in the comment section (since then, latest update with Ward Arguments completed, Sept 28, 2016, 8:55pm Pacific Coast Time):

Click on image to see easier and more clearly (better readability of the image).

Why I’m King James and the Contrast with a Dangerous King James Version Position

Like many English speaking people, I rely on the King James Version. I have biblical reasons. There are biblical reasons. The number one biblical reason is the doctrine of divine, perfect preservation of the text of scripture in the language in which it was written. The Bible teaches its own perfect preservation, including how it was to be and is preserved by God. This is also the historical view. The view I believe is also the view, the only view, of believers for centuries. The King James Version is translated from that text of scripture. There is no other English translation from that text. For that reason, I trust the King James Version.

Translation is good. Jesus translated. His translation was accepted as the Word of God. The apostles translated. God knew translation was necessary. God’s Word isn’t lost through translation. A major reason for this is that God created man in His image with the capacity of language. God created language. Adam and Eve spoke in the Garden of Eden from the get-go. Languages can be translated into other languages, because God created it that way. You can read Don Quixote in English and understand it, even though it was was originally written in Spanish. You can read The Art of War in English even though it was written in Chinese.

The only biblical position is that God preserved His Words, all of them and every one of them, in the language in which they were written. For purposes of this post, I’m focusing on “the language in which they were written.” If you believe that God has preserved His Word in the English language, then you do not believe the biblical and historical position. You don’t even believe in divine, perfect preservation. There is no way that you could. You deny preservation. You deny the biblical doctrine. You take a strange, new doctrine not even passed down by His people in true churches.

First, preservation entails preserving something. It preserves something that was there already. If it wasn’t there, it isn’t preservation. Translation itself is not preservation. What is preserved existed already. The English language didn’t exist in the first century. The English language began with the arrival of three Germanic tribes, the Angles, the Saxons, and the Jutes, crossing the North Sea from now Denmark to Britain during the 5th century AD. I stress, “began,” because there was still no English for quite awhile, because the Angles and the Saxons still needed to combine to the degree that a hybrid, AngloSaxon, could become a different and new language. That was Old English, which was English until 1100. As you observe it below, you will see that you cannot read it, because it is so different in nature than even Middle English.

The Bible has been perfectly preserved….

a. Somewhere in the abundance of all the manuscripts, the hand copies from copies of the original manuscripts.

b. In the underlying Hebrew and Greek text behind the King James Version.

c. In the English translation of the King James Version.

In studying the King James Version New Testament, I would primarily study the words by….

a. Finding what the underlying Greek word is and means.

b. Looking up the English word in the dictionary.

Let’s Be Very Clear: Not All King James Version Views Are the Same

A crafty way that multiple version (MV) or eclectic text (ET) advocates oppose the support of the King James Version is by lumping together all King James Version proponents as if they are all the same. There are extreme differences between different King James Version positions. To pick out the weakest, or even the strangest, a weird one, that has almost no veracity, and to knock it down, demolish it, doesn’t mean that you’ve actually proven much, if anything. And MV and ET defenders do mow down the worst of the KJVO (King James Version Only) and treat it like they’ve downed Goliath, included often times with strutting and trash-talking.

From the outside looking in, the MV/ET approach the odd KJV views like how upperclassmen, who still play freshman football, might pick on someone like themselves, but who plays on the junior high team. The upperclassmen are pathetic. Those KJVO aren’t reading you and those who do read you are not in any risk of reading them. Please leave them alone.

Ultimately, you just want to follow the truth and honor God, right? Isn’t that what you want? You aren’t trying only to win a debate or an argument. You want to take the position that represents God, what He’s said, right? So just because we are able easily to dispose of some far-out, non-historic, non-exegetical viewpoints, doesn’t mean that we’ve reached that goal. We haven’t even defended our own belief by doing away with other wrong beliefs.

So what are various King James Version positions?

I’m not going to attempt to label each of the views that people take, who support the King James Version, because the advocates will say I got it wrong. This will not come in any particular order.

Double Inspiration

Some believe that God has improved upon the original Hebrew and Greek by inspiring the Bible in English. Those who believe this say that the King James Version is the final edition of God’s inspiration and God chose to accomplish this in English. Obviously, these are people who support the King James Version and they’re King James Only, but they are much different than other iterations of KJVO. As I’ve read this type of KJVO and then MV/ET, I have found them to be very similar in their underlying error. They are both detached from bibliology.

English Preservation

Some teach that God preserved His Word by means of the English translation, the King James Version. They don’t believe that Scripture is preserved in the underlying text, because they would say that we don’t have a whole Greek text of the New Testament from which the King James Version was translated. The preservation of Scripture is found in the English, the King James Version. Any reference to the underlying Greek text is an attempt, it seems, to correct the KJV.

Majority or Byzantine Text

There are those who prefer the King James because it comes from the majority of the Greek manuscripts of the New Testament or from the Byzantine manuscripts of the New Testament. It became a standardized translation, so they prefer it. They don’t accept the modern versions, because those are influenced by the critical or eclectic text. They aren’t dogmatic about the King James Version. They just approve of it themselves without condemning people who use other translations.

Accurate English Translation of a Providentially Preserved Text

God preserved His Words, everyone of them, in the language in which they were written, and those Words have been accessible to every generation of believers. The King James Version is the best English translation of those Words and has been acceptable to churches. This position is buttressed upon biblical and historic teaching on the preservation of scripture. This position doesn’t say that every Word was preserved in any particular printed edition of the textus receptus previous to 1611, but that the perfectly preserved Hebrew, Greek, and Aramaic Words were received by and accessible to true churches (believers). Some have called this the “sacred text” position. I have called this the doctrine of the perfect preservation of scripture. This is the historic and biblical position.

I believe the fourth and last position here. I don’t believe the top three positions. There are many just like me. Most MV/ET advocates, who do not hold a historical or biblical view, argue against the proponents of either double inspiration or English preservation, and then they act as though they have shown what’s wrong with KJVO. They get back slaps and ‘atta-boys’ for having done so. They don’t fare so well when they have to take their positions into the consideration of careful exegesis of scripture. The just shall live by faith.

The Latin Vulgate and the King James Version

Latin Vulgate. King James Version. Two translations. How do you relate those two? The first is Latin, the second English. They are not translated from an identical original language text. The former was the Bible of Roman Catholicism, not a denomination that teaches salvation by grace through faith. The latter was accomplished by the Church of England with support and participation from professing Christians and ultimately accepted as the received version of Scripture by the English speaking people. Although it is called the authorized version, it was not actually authorized in any official way. It was referred to as the authorized version by the people. They saw it as authorized, so it became known as authorized.

Any other relations between the two? Probably a few others that don’t come to my mind. If you didn’t know Latin, the Latin Vulgate would be, well, Latin to you. It wouldn’t mean anything. It wouldn’t edify a non-Latin speaking people. You couldn’t say “Amen” to it unless you were fluent in Latin. It shouldn’t be your Bible unless you knew Latin. Latin wasn’t an original language of Scripture. Preservation of Scripture wouldn’t be the preservation of a Latin translation of the Bible. A denomination, like Roman Catholicism, could say that this Latin translation was the authoritative text of Scripture and that, my friends, would not be true. The authoritative text of Scripture would be an original language text.

Protestants and Baptists stood for an authoritative, original language text. Controversy arose between Roman Catholic theologians and Protestant ones over this issue. Romans Catholics came down on the side of the authority of the Latin Vulgate, for purposes of tradition, because it was the translation of the Roman church, and for biblical reasons Protestants and Baptists sided with the original language text.

As you read the previous two paragraphs, did you see anything that related between the position of the Catholics and the Protestants and Baptists? If you said “no,” that is correct. Catholics based their position on tradition. Protestants and Baptists in this case based their positions on Scripture.

In light of the above information so far, then how does the Latin Vulgate relate any more to the King James Version? Is the King James Version still supported by many Protestants and Baptists because of tradition like the Latin Vulgate was because of tradition? Could be by some, but that is not the historical position. Churches support and advocate the King James Version because of the original language words from which it derived.

Enter opponents of the King James Version, critical text proponents, or multiple-versionists. They tell the world that you see nearly identical relations of Roman Catholicism and the Latin Vulgate as of King James Onlyists and the King James Version. They are saying that the King James continues to be supported for the same reason the Roman Catholics required the Latin Vulgate. They are saying that King James Onlyists (KJO) are being Roman Catholic here. They claim that both the Roman Catholics and the KJO are the same in that they both look to one Bible. So they say that one-Bible-ism is Roman Catholic.

In my lifetime, I have mainly heard this type of argumentation coming from left-leaning or liberal who don’t have a good argument to stand on. Recently, Ann Romney, wife of Mitt Romney, wrote an op-ed, published in the Wall Street Journal, praising motherhood. In the next to last paragraphs, she wrote:

But no matter where we are or what we’re doing, one hat that moms never take off is the crown of motherhood.

Michelle Goldberg, an author and Newsweek contributor, took off on her “crown of motherhood” mention on MSNBC:

I found that phrase ‘the crown of motherhood’ really kind of creepy, not just because of its, like, somewhat you know, I mean, it’s kind of usually really authoritarian societies that give out like ‘The Cross of Motherhood,’ that give awards for big families. You know, Stalin did it, Hitler did it.

Multiple version supporters attempt to smear KJO by using the same type of argument, accusing them of a type of Roman Catholicism. That is exactly what it is, a hatchet job, that they really do know is not true. This type of argumentation works like a form of propaganda that is intended to intimidate. It works, not as any kind of credible proof, but as a way to embarrass someone to move from his position. It also tosses red meat to the supporters. They get a big kick out of it, just like the feminist panel got big chuckle-chuckles out of Goldberg’s snide remark about Ann Romney.

Those who use a Latin Vulgate attack either are ignorant of the position of KJO or of history, or are just devious. Protestants would not associate themselves with Roman Catholicism as some legitimate Western Christianity. Baptists never did. They rejected the Catholic position the Vulgate for the text received by the true churches, hence the received text. They applied this same title to the English translation from the received text by calling it the “received version” of God’s Word. By doing so, they referred to the text from which the translation came.

The longtime usage of the Latin Vulgate by Roman Catholics does not compare to the long time usage of the King James Version by actual Christians. Catholics required the Latin Vulgate. Until the freedoms originating from the Protestant Reformation, there was not widespread challenge to Roman Catholicism. The acceptance of the King James Version wasn’t forced upon anyone. The people received it because they were saved, Holy Spirit indwelt people. It’s history is one of choice, not of coercion. And that choice of God’s people testifies to the authenticity of the King James Version.

The Protestants and Baptists agreed that God had preserved all His Words, every one of them and all of them. They believed that there was one Bible, the one canonized by the Holy Spirit through His churches. This is the position found in the Westminster Confession and many other major confessions of those who believe in salvation by grace through faith. The Holy Spirit would testify to His people what His Words were and they agreed that those words were found in the Hebrew Masoretic and the Greek Textus Receptus. All accurate contemporary language translations from that text would be authentic.

The view of the Protestants and Baptists came out of a pre-enlightenment way of thinking, transcendent thought, that started with God and Who He was. They took a position that came out of the exegesis of Scripture, in complete contrast to Roman Catholicism.

The modern multiple-versionists represent a post-enlightenment thinking that begins with man’s reason. It does not rely upon the beliefs of God’s churches for centuries. Instead of depending on the Holy Spirit by faith, they reject what the churches received for the forensics of scientific theoriticians. They not only abandon an old and accepted Bible, but the testimony of the Holy Spirit through His churches. That’s why you will never, ever hear the actual historical, biblical position from them, even mentioning to you the pages and pages of well-established and documented bibliology of the pre-enlightenment saints. They reject historical bibliology for the uncertainty of textual “scientists.”

So when you hear these references to the Latin Vulgate in an attack on the King James Version, understand it for what it really is. It is a desperate smear from someone with no historical or biblical basis for his position.

The King James Version and the Doctrine of Separation

The Bible version issue will always cause division. Should it? Should believers separate from one another over what English (or Spanish) translation of the Bible they use? The answers to these questions have been percolating for awhile among fundamentalists. Certain recent events have caused the temperature to rise and some bubbling on the surface.

The Bible version issue will always cause division. Should it? Should believers separate from one another over what English (or Spanish) translation of the Bible they use? The answers to these questions have been percolating for awhile among fundamentalists. Certain recent events have caused the temperature to rise and some bubbling on the surface.

Northland and Matt Olson invited Rick Holland to preach in chapel. Kevin Bauder and Dave Doran are joining Mark Dever on the platform of Tim Jordan and Calvary Baptist Theological Seminary. To explain, Matt Olson sends out a public letter and preaches a couple of chapel sermons, and Kevin Bauder writes a now 24 part series, which publishes at SharperIron. How do these relate to the Bible version issue? That’s probably hard to figure out if you didn’t know fundamentalist politics. Here’s the gist of it: KJVO (King James Version Only) fundamentalists are worse than Holland and Dever, which explains Bauder and Olson’s fellowship with Holland and Dever—if fundamentalism doesn’t cut out its KJVOists then Holland and Dever shouldn’t be a problem. Or stated differently: if they’re closer to Holland and Dever than these KJVOists, then they’ll just get together with Holland and Dever. If someone is going to criticize them for Holland and Dever, then someone may need to criticize John Vaughn for preaching with Clarence Sexton and Jack Schaap. So there we go.

I don’t really care if Northland has Olson or Bauder speaks with Dever. I don’t. It doesn’t change anything for me as it relates to those two men and their institutions. However, I have to say something about the way the Bible version issue is being represented as a part of their explanation for getting there. I see at least four parts to the problem. Not necessarily in this order, but, first, schismatics, second, bibliology, third, history, and, fourth, stupidity. These events and then proceeding debate indicates the impossibility in fundamentalism to sort out unity and separation.

Schismatics

In the debate that followed the publishing of Bauder’s article at SharperIron, the charge of schismaticism against KJVOers was used as a reason for separating from them. In other words, many KJVOers are schismatics, that is, they cause division over the Bible version issue. The correct position would be not dividing over differences in Bible version. According to them, it is permissible to divide over certain doctrines, but not that one. If you do, you’re a schismatic.

One wrote this:

The real issue is divisiveness. If a KJVOer mistakenly believes only one translation has value, it is a relatively minor problem. If he is divisive, demanding that everyone agree, etc, the minor problem becomes major. But the problem isn’t really his view on translations, but his divisiveness — a problem of the heart not the head, a problem of pride.

I believe this comment represents what fundamentalists are saying about schismatics over Bible versions. Is what he writes true? He is saying that differing on the Word of God is acceptable, but dividing over it isn’t. He is saying that you’re not wrong to differ on what the Word of God is, but you are wrong to divide over the differences. He is saying that you can’t divide over the usage of the ESV or NIV without being a schismatic. Why? Where does Scripture tell us this? What passage in the Bible do we base this upon? I’d like to know.

From reading Bauder’s latest article, I’m supposed to understand that we’ve got no problem with fellowship despite a different mode or recipient of baptism, but I do if I separate over Bible versions. And none of this is supposed to be confusing? It’s only not confusing if you have a handle on fundamentalist politics. Knowing the Bible won’t help you at all with getting how they come to make their decisions on separation and unity.

“Schismatic” relates to division, and division is a church (local) issue—period. A heretic, a schismatic, causes division in his church (see Titus 3:10-11). Division in “fundamentalism” or “evangelicalism” or in a certain branch of fundamentalism isn’t heresy or schismaticism. They throw schismatic around like the pope threw around the term “heretic” during the Spanish inquisition. These people want to bring people into line with their own sacral society with their use of the label “heretic” or “schismatic,” just like the pope did. I suggest that everyone just ignore this concept of division or heresy or schismatic. This fundamentalist false view of unity is much more dangerous than a division over Bible versions. These are men that can’t persuade of their position on Bible versions, so they use these labels to frighten people, just like the pope did.

Bibliology

The issue of Bible versions is a matter of faith. #1, does the Bible teach that God would preserve every Word? Answer: yes. #2, does the Bible teach that every Word would be available for every Christian of every generation? Answer: yes. #3, does the Bible teach that God’s Word would be perfect? Answer: yes.

If you have the text behind a version with 7% variation from another one, they can’t both be the same. With what I see the Bible teach about preservation, I can’t overlook the variation. I can’t say they are the same. I won’t say they are the same. I won’t say they are the same like I won’t say that rock music and classical music are the same. They are not. I can’t say the differences don’t matter. God inspired every Word.

There is no way that the text that is the basis for the modern versions could be the Words of God. They can’t. They weren’t available for hundreds and hundreds of years. That would conflict with what the Bible teaches about its own preservation.

The Bible version issue is a doctrinal one. The modern version people don’t believe what the Bible says about itself. At the most, they will say that they believe that God has preserved every Word in the multiplicity of the manuscripts, but upon further investigation, you will find that they don’t even believe that. Most, if not all, don’t believe we have a manuscript with the words of 1 Samuel 13:1 in it. Mike Harding wrote in God’s Word in Our Hands (p. 361):

I believe the original Hebrew text (of 1 Samuel 13:1) also reads “thirty,” even though we do not currently possess a Hebrew manuscript with that reading.

So they don’t even believe #1. And they don’t believe #2 and #3. And what do #1, #2, and #3 have to do with the authority of Scripture? They would say that the errors in what they possess don’t affect authority. They know they do. Everyone knows they do. The uncertainty about the Words takes away from authority.

You get beliefs #1, #2, and #3 from Scripture. So if you don’t believe those, where are you getting your beliefs on those? You aren’t getting them from the Bible. They get upset if we say they are getting them from rationalism, when there seems to be a load of evidence that say they do. Does it matter how they got them? I think it would be helpful for them to try to connect the dots. I think they are easy to connect, but why not start with placing faith in what God said?

So when I separate, I separate over these doctrines. You can’t be a modern or multiple version person and not reject at least #2 and #3. Is less than a perfect Bible a separating issue? Doesn’t a rejection of those doctrines reflect on the veracity of God too, since He inspired those doctrines? Will propagating a false doctrine or even just accepting a false doctrine on these have an impact on people? Does it affect the Great Commission, which says that we are to teach the new believers all things that Jesus commanded? If we get blessing from reading all the Words of the prophecy of Revelation (1:3), will people not get the blessing God promised if they read only some of the Words?

Mike Harding cut and pasted this in response to Bauder’s article:

The FBFI affirms the orthodox, historic, and, most importantly, Biblical doctrine of inspiration, affirming everything the Bible claims for itself, and rejecting, as a violation of Revelation 22:18-19, any so-called doctrine, teaching, or position concerning inspiration, preservation, or translation that goes beyond the specific claims of Scripture.

The use of Revelation 22:18-19 is clever, especially since those verses warn against adding or taking away from the words of the book, not the doctrines of the book. They misuse a verse, which is actually about preservation of Scripture, against the doctrine of preservation. What they’re saying, of course, is that the claim of perfect preservation of Scripture goes against the teaching of the Bible. I just wag my head.

I believe that these bibliological doctrines are more important than my association with modern or multiple version men. What God said is more important than them. They can call me a schismatic. I’m sorry about that. I’m just not going to be able to allow that to have an effect on me. So I won’t let it.

History

Mike Harding wrote this:

Bauder’s article pointed out that a significant element in the fundamental movement holds to the KJVO position and that some do so in such a fashion that is doctrinally aberrant or historically misinformed.

I’ve read this type of comment from many fundamentalists. They are the ones who are either ignorant or rebellious against historical evidence. The modern or multiple version position is the new position. Every word perfection in the apographa is the historical position. It is true that fundamentalism has accepted critical text advocates, but that is a movement a little over 100 years old. That is the historical argument of God’s Word in our Hands, of which Harding was one author, and then God’s Word Preserved, by Mike Sproul. Their historical, textual arguments go back around a century. That’s it. That doesn’t present really any kind of historical argument. So they have a doctrine that isn’t in the Bible and can’t be backed up in history.

Someone else commented later:

Hundreds of young people are continually led astray and given a fraudulent view of history and Christian certainty of truth.

The fraudulent view of history is the modern or multiple version position. It isn’t found in Scripture or in history. Neither is it logical—two things that are different cannot be the same. It is true that men have written against the preservation of Scripture. They have also written against inspiration, against the deity of Christ, and against other true biblical doctrines. That doesn’t make what they have written to be true. When you speak to Islamics, they are some of the greatest advocates of the critical text and copyist errors in the Bible. Their writings are in books, pamphlets, and all over the internet.

Stupidity

As the part of the context of a previous comment, Harding also wrote:

Enough ink has been spilled on this issue to correct the problem, and yet the problem dogmatically persists. The KJVO movement in its various forms was never a part of historic, biblical fundamentalism.

A regular feature of fundamentalist criticism of KJVO is that KJVOers are stupid. They try and try to explain, but these knuckleheads just don’t get it. This is a fundamental aspect to the problem of fundamentalism with KJVO. The fellow KJVO fundamentalists make them look bad with their “fellow scholars.” It is more important to fit into scholarship than just to believe the Bible and what it says about preservation. The same kind of criticism comes from scientists about young-earthers, who don’t believe in evolution. The issues are very similar in nature. Both critical text supporters and old-earth creationists have altered the historical, biblical views to fit into science. They have changed doctrine in light of new human discovery.

Intellectual pride always causes problems. It’s a sin in itself, but it will result in further error, both doctrinal and practical.

Someone else wrote:

The arguments for the KJVO, and some KJVP, positions have now been thoroughly exposed and refuted many times. Yet the Pastors and leaders in the KJVO movement continue to side step common reality and seek to offer the same old mis information and factually wrong history.

Here you get the same history criticism with the addition of a subtle stupidity one. KJVOers “side step common reality,” even though their position has “been thoroughly exposed and refuted many times.” The reason they don’t change is because they need a scriptural position and explanation. They would also like to see where Christians have believed the same further back than 100-150 years. It’s not because they are stupid.

Conclusion

Churches will separate over doctrine and practice (Romans 16:17-18). They should. There is nothing more fundamental in the realm of separation over doctrine than “errors in Scripture.” If someone says there are errors, our church says that is false doctrine. We will separate over that. We want to preserve and propagate the doctrine of preservation and availability and perfection of Scripture. One of the biblical means for doing that is separation.

Addendum 1

Kevin Bauder wrote a comment after the most recent post in his 24 part series. He wrote:

The most egregious error is the one that Sexton advocates. The New American Standard Version is the Word of God. The New International Version is the Word of God. The English Standard Version is the Word of God. For someone to insist that they are not is to show contempt for the Word of God. I believe that this is grave error, every bit as serious as anything that Billy Graham has done.

In my opinion, this is mere game-playing. I think we have good reason not to share a platform or fellowship with Clarence Sexton that relates to defense of the gospel. However, if we were to say that the NASV was not the Word of God with the explanation that it comes from a corrupt text, a text not received but rejected by the churches, how does that not respect the Word of God? This is where we have game-playing on the part of Bauder. For instance, I would say that the NASV is the Word of God where it represents the text received by the churches, but not so where it has been corrupted. Do we have to call what we think is a corrupt text the Word of God? If not, we disrespect the Word of God? Wow. Who really is disrespecting the Word of God?

I don’t believe this is ultimately about the Bible or translations as it is holding together a coalition of men who use a wide variety of translations. Everyone must call each translation the equal, when they are actually not equal. They couldn’t be, when they are different words. This is an attack on the inspiration, preservation, and authority of Scripture. Why? Because God inspired Words. Words that are different can’t both be inspired. That is obvious, which is why what Bauder is doing is game playing. For instance, what if we added the apocrypha. Is that the Word of God? Are deletions or additions the Word of God? It seems that Kevin Bauder must have a faulty bibliology be the thing that he most seriously disrespects about Clarence Sexton, even though Sexton would probably say something similar to what I wrote about the NASV. And yet, the infant sprinkling of a Presbyterian is a lesser problem for him.

Addendum 2

Several comments to the last two Bauder articles say that the NKJV is the same text, the identical Greek words to the TR. This is an error that should stop.

Jude 1:19, the MV/C text omits eautou (“themselves”), as does the NKJV.

Acts 19:39, the the NKJV follows the MV/C text in “peraiterw” instead of “peri eterwn”, subtle but different.

Acts 19:9, the NKJV follows the MV/C text in omitting “tinos.”

Acts 17:14, the NKJV omits “as it were” (“ws” in the Greek) and thus once again follows the MV/C text.

Acts 15:23, the NKJV follows the MV/C text in omitting “tade”, or “after this manner.”

Acts 10:7 the NKJV follows the MV/C text in omitting “unto Cornelius” in the first clause.

Addendum 3

Another error propagated in comments to the last two Bauder articles is that the belief in perfect preservation is the same as believing in double inspiration. One commenter wrote:

There is really no difference between a Ruckmanite and someone who believes that God’s Word is preserved perfectly only in one of the TR texts.

This is patently false. I won’t call it a lie, just someone trying to say something impressively extreme, in complete ignorance. If you have the same words as the those originally inspired in the Greek and Hebrew, that is called preservation. The words don’t need to be given by God again, because they already exist and have been preserved. The false doctrine of double inspiration deals with English words, because God didn’t inspire English words. These types of errors are then congratulated and no one points out the error. And this group talks about false bibliology. Can they be trusted?

Was the King James Version the Standard for the English Speaking People for 300 Years?

Recently in a comment section of a blog post, someone (an Erik DiVietro) asserted that the King James Version was not dethroned as the standard for the English language only because of authoritarian government control. That didn’t sound right to me. It was something that I hadn’t read. Now I had not read much on this, I didn’t think. I’ve read a couple of the histories of the King James Version, without cherry-picking my sources. But also I’ve seen comments in many other books that took the position that the King James Version was the standard for the English speaking people for at least three hundred years. I’ve read this point in books by those espousing a different New Testament text than that of the King James Version, not just rabid King James supporters. It’s all I’ve read. My understanding was that God’s people loved the King James Version.

Recently in a comment section of a blog post, someone (an Erik DiVietro) asserted that the King James Version was not dethroned as the standard for the English language only because of authoritarian government control. That didn’t sound right to me. It was something that I hadn’t read. Now I had not read much on this, I didn’t think. I’ve read a couple of the histories of the King James Version, without cherry-picking my sources. But also I’ve seen comments in many other books that took the position that the King James Version was the standard for the English speaking people for at least three hundred years. I’ve read this point in books by those espousing a different New Testament text than that of the King James Version, not just rabid King James supporters. It’s all I’ve read. My understanding was that God’s people loved the King James Version.

Here’s the key portion of the comment:

Your argument breaks down because in the period you’re describing, the KJV was the Bible of the English-speaking people because there was no other permitted translation. In the British Empire, it was illegal to use any other translation of the Bible. Any new effort at translation had to be disguised as a ‘paraphrase’ and even then the opposition was intense. And any suggestion of revision or retranslation was stoutly opposed not by your group of the faithful but by the academic, political and religious elites.

The English-speaking scholars of your period of use were already arguing for a revision of the Greek text, and by necessity the English. Here’s (sic) just a few items to note:

* In 1684, Richard Baxter was imprisoned for paraphrasing the New Testament.

* Daniel Mace, a NT scholar, printed a colloquial translation of the Scriptures in 1729; but his work was ignored because 1) he was a Presbyterian and 2) his translation dared to use current language.

* Richard Bently of Cambridge proposed to restore the text of the New Testament by “By taking two thousands errors out of the Pope’s Vulgate, and as many out of the Protestant Pope Stephen’s…” His Protestant Pop (sic) Stephen is the editor of the Stephanus 1550 textus receptus.

* In 1731, Leonard Twells wrote a call for correcting Stephanus and was literally shouted down by the Anglican Church.

* As early as 1741, Robert Lowth was calling for a revision of the KJV translation of Hebrew poetry because it did not take into consideration what was becoming known about the workings of said poetry.

* There were somewhere around 40-45 translations into English of the whole Bible, books or sections done between 1700 and 1800.

* It was Archbishop Thomas Secker who sidelined the idea of revising the KJV in the early 1760’s. At that time, it was being seriously by many scholars. (I cite Neil Hitchin’s 1999 essay on “The Politics of English Bible Translation in Georgian Britain” for further notes.)In short, it was not your God-fearing remnant who kept the KJV in print and refused any kind of revision. It was the monstrous behemoth that is the Anglican Church.

I will conclude with also pointing out that during this entire time (from the first printing of the KJV in 1611 until the American War for Independence), there were something like 65 different British editions of the KJV floating around – all with variants that were confusing and frustrating. Not surprisingly, the Americans were almost completely cut out of printing Bibles, having to import them from the Crown-licensed printers.

So much so that in 1790, Isaiah Thomas – an American printer – compiled every edition he could find and produced a new edition reconciling the editions. (By the way, Thomas’ work was masterful and the basis of all American editions since.)

The young man (an Erik DiVietro) writing the comment called himself a historian, that he was a historian of the English language. With a lot of bluster, he showed irritation that his documented history was not taken seriously. I’ve read a lot of history, in part because I’ve taught history for over 20 years. I don’t consider myself an expert at any particular area of history. I’m willing to bow to someone else’s expertise. However, neither am I naive. I was willing to give this point of view a hearing. Now I do know when I am reading something that is persuasive and then trustworthy. I have a pretty good handle on judging sources. I am very suspect if I hear something new like this view that he was promoting. Historians are usually biased. They often must be taken with a grain of salt. But again, if I’m going to learn, I’ve got to be open minded.

This self-professed historian of the English language suggested that I would be greatly helped if I read two sources that he recommended, one a lengthy book on the history of the Bible in the English language and the other an article which first appeared in the Royal Historical Society publication in 1998. I obtained both of those books that represented the deep research that swayed this young man, who considers himself to be an expert in this field. By the way, if someone is recommending just two sources, the two that agree with one another, I’m already questioning what’s happening. Any historian would. This is supposed to overturn the only position that I’ve heard.

In the book he exalted as the supreme source to understand the history of the King James Version, The Bible in English by David Daniell, I found the author to be very biased, ridiculously so and obviously so. His sources were not convincing. I was left with the observation that this man had a bone to pick with those who support the King James Version. I will show how what he wrote reveals this. The other source was the article, The Politics of English Bible Translation in Georgian Britain by Neil W. Hitchin. In his second sentence, Hitchen writes:

The long tenure of the King James, or Authorised Version (AV), has caused historians to overlook the existence of the scores of translations which were attempted between 1611 and 1881-1885, when the Revised Version was published.

First, I challenge the premise here that historians overlooked other translations made. Hitchen had plenty of source material to show these translations. Others have made note of these, belying the idea that historians overlooked them. Second, they weren’t “attempted”—the translations were completed. They weren’t accepted—that’s different than being just attempted. In a footnote (fn 8) Hitchen mentions books on the history of the English Bible that either make no point of eighteenth century English translations or as he asserts, “lack an interpretive scheme.” He decries the lack of interpretation for the rejection of these translations. Perhaps there was no “interpretive scheme” because no interpretation should have been made. Their dismissal should have been taken at face value.

Hitchen’s article centers on “an unsuccessful campaign to get the Crown to convene a committee to produce a new authorised version.” Concerning those who wanted this translation, Hitchen writes:

The dissenter’s support for a new official version seems to reflect an assurance that they had a stake in the nation’s religious life. If so, theirs was a sophisticated use of a key national text to redefine the assumptions of national religious culture either to obtain the limited goal of toleration for themselves.

This should give some hint as to why none of these translations was accepted. Hitchen describes the attempt of a new translation (p. 78):

[T]he ideology of nature was quietly displacing the reformation ideology . . . in the modern idea of ‘science’ being applied to biblical texts. The substance and style of early eighteenth century divinity were modelled on scientific precision and sobriety. . . . Jones described a critical technique which treated the Bible as a parallel of nature and the biblical student as a scientist. In early 1789 Edward King’s Morals of Criticism advocated an ‘application of modern science to biblical texts’, which his reviewer found ‘very interesting’.

We should be happy that a new translation based on these premises was not accepted.

The young historian with which I had my discussion talks as though powerful forces worked against a new translation. Hitchen, speaking of those who had an influence on Archbishop Secker, referred to Benjamin Kennicott, who “expanded the textual knowledge of the Hebrew bible vastly, supported by money from the king.” Kennicott (pp. 86-87) “concluded in 1780 by saying that ‘none of the variants was a threat to essential doctrine or increased historical knowledge.'” That doesn’t sound like some political conspiracy against a translation. In his conclusion, Hitchen says:

The point at issue in the debate over the English version was whether the old translation illuminated or obscured the Gospel, and whether a new one was likely to be hijacked by heretics. All sides had doctrinal agendas.

This was not a point of authoritarian power being abused, the idea the young “historian” wanted to read into the rejection of a new English translation.

It is helpful to look at the source from which the young man tries to find conspiracies where there are none. The young man mentions Richard Baxter being thrown into jail for making a paraphrase. That is true, but the context of that situation was very local, not national—the case of an over-eager and biased judge overreaching his authority. Nothing more came of it. He says that Daniel Mace had his work ignored because he was a Presbyterian and because the English was too current. He takes this conclusion from Daniell’s book, a man who we cannot rely upon for an unbiased view of the King James. Daniell’s “historical” position about the King James comes from one major source: Bruce Metzger. When Daniell criticizes the poor textual basis of the King James, he is not making a historical judgment. He takes that from reading Bruce Metzger’s twentieth century work of textual criticism. After a quotation of Metzger on p. 510 to criticize the New Testament text behind the King James Version, Daniell writes:

One of the curiosities of Bible history is the superstition about this text, a rigid religious loyalty of many Christian to this textual monstrosity that to try to amend it, or even criticise it, has been branded as near-sacrilege — indeed, still is, in some places.

And then in a footnote attached to this particular sentence, Daniell recounts a story that helps us understand his feelings:

I myself have been publicly reviled for speaking well of Wescott and Hort, the scholarly makers of the pioneering 1881 two volume The New Testament in Original Greek, not knowing that I could in any way be giving offence to a member of a North American lecture audience in the late 1990s. For her, the Textus Receptus was the Word of God.

Can you imagine a “historian” including such an anecdote in the midst of what is supposed to be history? I guess if someone is preaching to the choir, it would be well-accepted. As far as Daniel Mace is concerned, first concerning his “current” English, Luther A. Wiegle of Yale Divinity school regretted Mace’s “pert colloquial style which was then fashionable” (p. 509). Mace lost his influence where he was, not because he was a Presbyterian, but because “local congregations were suscepitble to Whitefield’s and Wesley’s gospel fire” and “in that time [Mace’s] flock dwindled.” The work of the gospel was a reason for the rejection of Mace. Isn’t that a good thing?

As you look at much of the source for Daniell’s material about textual revision, you read Bruce Metzger (including the Bentley quote about “Pop (sic) Stephanus”). So we don’t have any kind of fresh hardcore uncovering of a conspiracy afoot regarding the acceptance of the King James Version as the standard for the English speaking people.

The young historian says that Leonard Twells had written a call for the correction of Stephanus. It is absolutely just the opposite. When Mace attempted to challenge the textus receptus, Twells wrote a defense, published in three volumes in London, against Mace’s text, entitled: A Critical Examination of the late Testament and Version of the New Testament: wherein the Editor’s Corrupt Text, False Version and Fallacious Notes are Detected and Censur’d. It really is a joke that he would use Twells as a basis for dislike of the textus receptus, when the man wrote a three volume series both defending it and then criticizing the edits of Daniel Mace.

The young historian writes that Robert Lowth was calling for a revision of the KJV because of his expertise on Hebrew poetry. No. Daniell himself writes (p. 516):

Scholarly understanding of the nature of Hebrew poetry, following Robert Lowth in 1741, was one reason for increasing calls for revision of KJV.

Daniell does not give any evidence of Lowth calling for a “revision of the KJV,” just that men were calling for a revision based on Lowth’s work—again, not Lowth himself. This is just a blatant falsehood by the young “historian,” perhaps with the hopes that no one would check him out.

Later in his book, the supposedly trustworthy Daniell, with reference to Lowth, makes these comments about men’s attitudes about the KJV in the mid eighteenth century: